“Tomorrow Will Be Better”

By Nina Verheul

The photo exhibition “Tomorrow Will Be Better” by the Polish photographer Tadeusz Rolke was held from August 2016 till May 2017 at the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe (hereinafter referred to as the Center) in Lviv, Ukraine. The photographs tell the story of Lviv’s transformation in the period 1989—1991, that is just before the fall of the Soviet Union, the former federation of fifteen communist republics between 1919 and 1991. Rolke traveled to Lviv on behalf of the German magazine GEO to document the determining events and changing ambience of the urban space, and always with regard to the everyday life. The final photo-series represents a historical documenting of the transition period, reproducing the crossroads between the Soviet presence and the prospective feeling of independence. Those years can be described best as a period of big shocks and changes: from a closed public society (both in terms of borders and in terms of communication) with a controlled and organized daily life, Ukrainian society became one of promises, dreams and hope. The opening of the borders meant free movement, new experiences, external influences and a richer cultural life with place for both international and Ukrainian traditions. Yet, the need to build up an own life involved a new fear of the unknown too. The benefit of free education and health service made space for a financial crisis with high inflation and a shortage of goods. “Tomorrow Will Be Better”, therefore, has a double meaning. Tomorrow does not only refer to a future independence, seen from Soviet time, yet also reproduces Ukraine’s struggle of living independently. Certainly, Ukrainian independence did mean it was not anymore determined and regulated, yet being free and independent also meant an effort to go back to square one. Precisely this feeling of “emptiness” between the Soviet era and the independence is represented in Rolke’s photographs.

“Tomorrow Will Be Better” goes beyond that what is told by history books: it is about the everyday life of Lviv’s people. This fits in the Center’s aim to tell a completer history that is told from a broader and more bottom-up perspective instead of a top-down one. This so-called microhistory, emphasizing personal stories and everyday-life, shifts the focus from mere facts and dates to the actual, yet unknown, people that lived through history. Not only would heroic stories slowly make room for “forgotten” histories, but this shift would also let more different people feel included in a society’s memory. In other words, memory would become a product of the people instead of a product of politics (Van Free 2013: 2). New, debatable histories could eventually open up frameworks that are currently less discussible (Van Vree 2013: 7). With regard to this particular history of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, it is imperative to breach the culture of silence whereby certain negative aspects of Soviet rule are still unspoken. The Center’s educational program alongside the exhibition encouraged students to think of alternative ways of historical thinking and to hold conversations with the older generation that experienced the Ukrainian Soviet time. This focus on communication and history education could contribute to an establishment of new frameworks. Developments such as these ones prove a change in current Ukrainian society, where there is more place for open critique on, for example, conscious historical oblivion or political dishonesty.

Podcast

Van Vree, F. (2013). Absent Memories. Cultural Analysis, 12, 1-12.

Uniting a Divided Country?

Examining the role The Centre for Urban Studies of East Central Europe plays in forming Ukrainian identity

By Amanda Smith

Ukraine’s borders have changed many times over the centuries and so the fringes contain a collective of different cultures. Take a look around Lviv and you will hear many Polish voices and see a re-emerging Jewish past filtering into the Old Town. Despite living side-by-side, the cultures do not mesh comfortably and anti-Semitic vandalism occasionally appears at sites of Jewish remembrance.

Photograph – Amanda Smith

In addition to these minorities is the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine which appears to be struggling to carve its own niche in a part of the country which is apparently increasingly pro-EU. Aside from the current internal conflict of identity, the country is still struggling to deal with atrocities committed by Ukrainians on the Jewish community during the Second World War, and with events which followed under Stalinist rule. Due to this uncomfortable legacy, these histories have been silenced, and it is only since Ukrainian independence that a dialogue has emerged. As part of the Heritage and Memory course, my intention in Lviv was to examine to what extent ‘identity’ is affected by changing borders, and to what extent a cultural institution can play a role in shaping, or even creating, an open, multi-cultural, border Ukrainian identity.

Seeking the “Ukrainian” Identity and visiting the Urban Centre

Largely, this search for “Ukrainian identity” was instigated by reading ‘Ukrainian Lviv since 1991 – a city of selective memories’ (2011) by the French academic, Delphine Bechtel. In it she claims that Ukraine has been searching for one

narrative which would show a continuous and uninterrupted Ukrainian past […] updating of the city’s history to the almost complete exclusion of the Polish, Jewish and Soviet/Russian part of the city’s history. [1]

In our increasingly globalised, multi-cultural societies, this is a rather problematic statement. Further probing Bechtel’s bold perspective, I chose to examine the Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe (often shortened to the Lviv Urban Centre). They are a private, non-profit organisation which aims to prevent history from being used for political agendas, while also promoting accessible learning for all. [2] Whilst multi-cultural exclusion is not necessarily something which forms part of the Ukrainian government’s contemporary agenda, the Urban Centre is an organisation which actively takes action against this reoccurring in the future by dissecting the past.

Having seen from the Urban Centre’s website that it often collaborated with Polish artists on various projects, [3] disparity arose between Bechtel’s article and what could be seen taking place at this particular organisation. Although emphasising that that they do not represent all Ukrainians but merely conduct research and display the results, [4] the Urban Centre appears to reflect a broad spectrum of people – not only those from Ukraine but also from the neighbouring countries. Additionally, the centre is at the heart of many urban heritage and regeneration projects in Lviv. Their latest art exhibition – intriguingly titled “[un]named” – taps into the silenced histories of Lviv and it is here that I bore witness to a more multi-cultural aspect of Lviv.

My and Nina Verheul’s podcast examines the Urban Centre in more detail and what we encountered when we visited the Urban Centre’s exhibitions “Tomorrow Will Be Better” and “[un]named”.

Analysing the “[un]named” Exhibition

Formed in 2003, the Urban Centre, located close to the heart of Lviv’s Old Town, is situated within an early twentieth-century apartment building. Although it is first and foremost a research centre, a basement tucked away beside a small courtyard affords the Centre a modest exhibition space and it is here that the previously-silenced histories of Ukraine are unfolded in “[un]”named. Largely concerning tragic events which took place during the Second World War and in the unfolding Stalinism of the 1940s, the exhibition, created by the Kyiv-born artist, Nikita Kadan, depicts victimhood and perpetrators of these atrocities. The art is further supplemented by mini-essays written by people from varying academic disciplines and nationalities.

Venturing below the ground level of the Centre to find the exhibition, I bore in mind the theorist Stephanie Moser’s work “The Devil is in the Detail” where she states that every part of an exhibition has been carefully considered and has layers of meaning. [5] Descending into the basement gives the sensation that, like the past, even this exhibition has been hidden away, as there was no tangible literature either inside or outside the building’s entrance to attract a potential visitor to ”[un]named”.

Resembling an x-ray lightbox, wall panels featuring introductory text to the exhibition illuminate the entrance space; later in the exhibition, flat panels containing short papers written by various philosophers, historians and other academics from around the world can only be seen by the visitor by pressing a button to illuminate the darkened panels. When considered together, these features imply a sense of unearthing something hidden, something forensic and factual, and it is only by exploring in the darkness that the visitor will uncover something hidden beneath the layers.

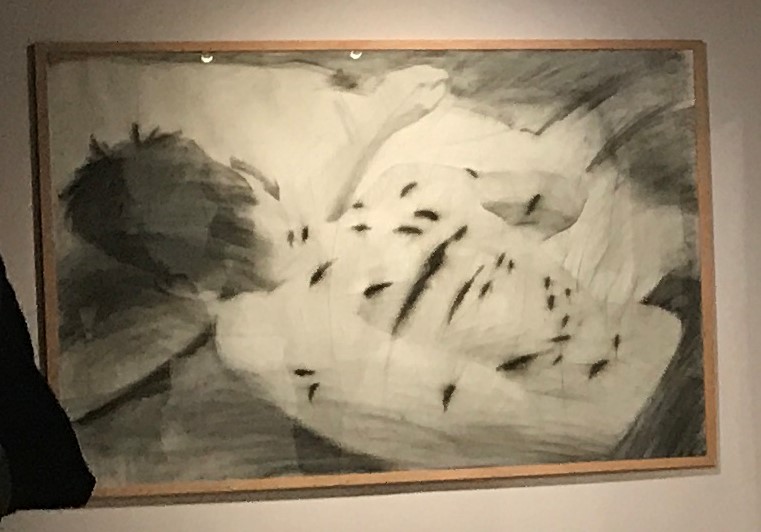

A wall-spanning triptych entitled “National Landscape” instantly faces the visitor in the first gallery space, featuring a long, wide road and empty, overgrown fields. Throughout the exhibition Kadan uses a very monochrome palette and so the triptych looks bleak and empty. To the uninitiated in the history of Ukraine (such as myself!), the long road initially suggested that this was perhaps a comment on the future of Ukraine. However, after spending the following days walking around a host of former Lvivian Second World War campscapes and witnessing the empty, largely unmarked areas where mass extermination had taken place, my perspective on Kadan’s triptych was slightly altered. These mass graves were not always demarcated, overgrown and often littered.

I later learned from Professor Iryna Starovoyt of the Lviv Ukrainian Catholic University that she believed Kadan’s empty fields were representative of unmarked mass graves. [6] To an outsider to the culture, this layer of meaning could go completely unnoticed and thus the silenced history, at least within this set of paintings, continues unchallenged.

The exhibition is critical of the reliability of history and selective remembering. Kadan was inspired to create this series when he discovered a photograph on the internet labelled “Ukrainian peasant killed by Poles”. He then found that forty years after the photograph’s original publication that it had reappeared in a different newspaper, but this time with the nationalities of the victim and perpetrator reversed to suit a different political purpose. The theme of his exhibition complemented the Urban Centre’s mission statement to “prevent history from being abused for political ends,” and so the two decided to work together. [7] However, despite these noble aims, the nature of the content of “[un]named” remains highly politicised and emotionally charged.

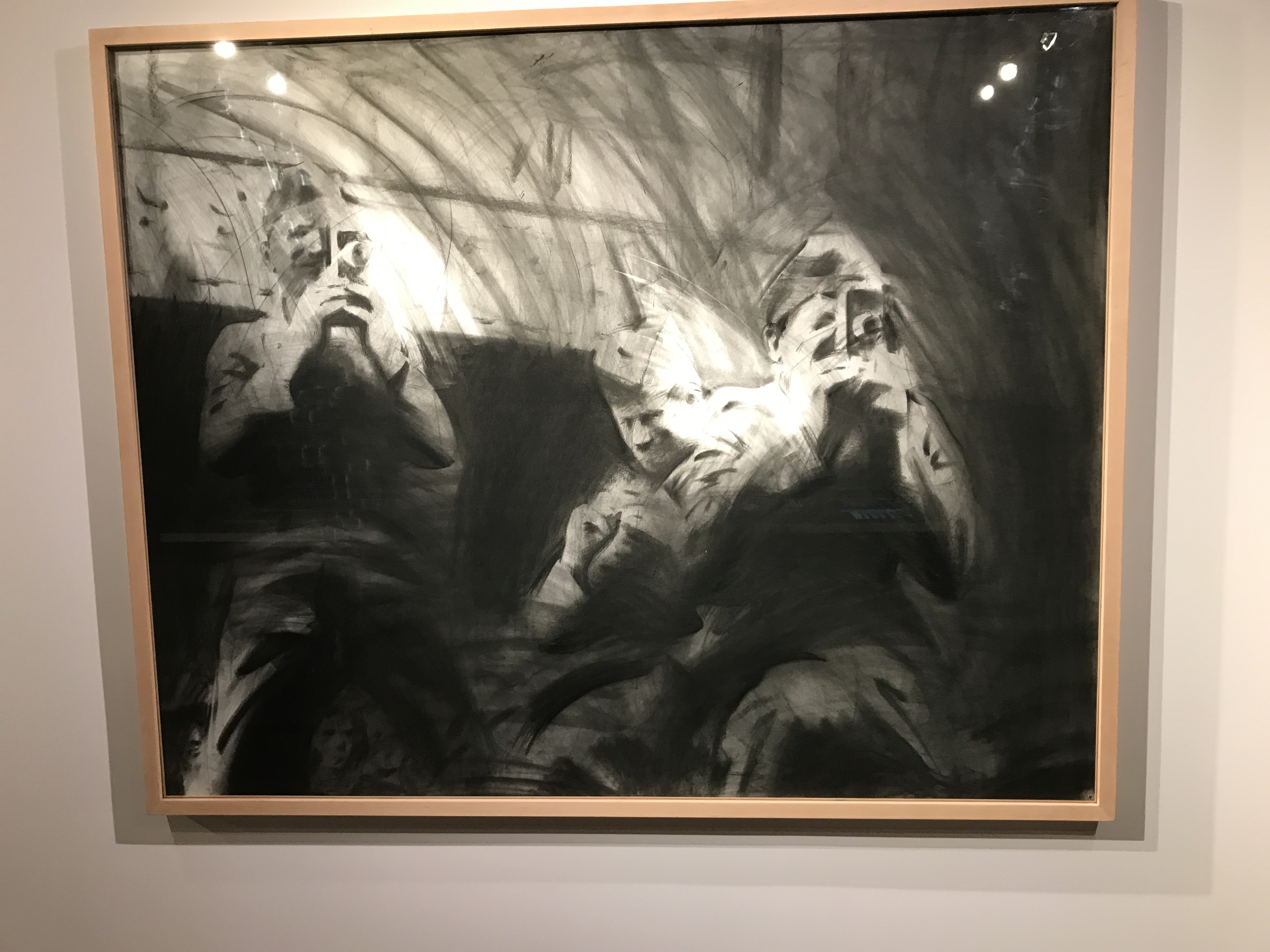

Where the exhibition excels is in unifying the onlooker with the pictures by leaving the faces which are depicted with few defining facial features. By painting people in this way, it creates a space where the viewer can more easily place themselves in the position of the victims. Instances where this is most notable is the contrast between the victims and the perpetrators.

The victims are vulnerable, their faces exposed, whereas the perpetrators are given distinct uniforms and have their faces obscured by cameras. Fascinatingly, the placement of this painting in the mid-section of a horseshoe-shape means that the soldiers appear to be taking pictures of the violence being depicted in the surrounding paintings. Whereas the victims are given just enough facial detail to allow the viewer to empathise with them, the cameras which the soldiers hold places a physical boundary between the viewer and the perpetrator figures. The soldiers’ stance is intimidating and it places the viewer in the position of the victim – they become the exposed, vulnerable person being examined and photographed. Via the invisible line between the soldiers facing the victims, the viewer of the painting is forced into the position of the perpetrators and becomes complicit in witnessing the violent act. This duality of the visitor’s gaze causes them to question their own gaze and their stance – which side do they belong to?

National Identity and the Exhibition

By presenting the visitors with such confronting images and getting them to indirectly participate with the art, the exhibition creates a connection between visitor and painting, provoking conversation and providing an opportunity for the contested history to be discussed and deconstructed. In a supplementary text to the exhibition, the Ukrainian psychoanalyst, Roman Kechur, mentions that:

mourning [the past] is necessary to experience the loss […] not to brush it off and forget, but to focus on and live in the new reality. […] Only by experiencing sorrow can one move forward, and keep the future from being an endless yesterday. [8]

Kechur suggests that it is only by breaking down the past, thereby deconstructing the current perception of identity, that the country can then move forward. However, as I found during my time in Lviv, strong patriotism plays a role in the construction of the contemporary Ukrainian identity. It is this strong nationalist faith which stands behind the silencing of the past and, surprisingly, it is not an issue solely constrained to the older generation. Even some of the younger Ukrainians have a problem with engaging with a problematic past; some students who I encountered at the Ukrainian Catholic University saw no point in dwelling on the past but instead preferred to forge ahead without looking back. [9] Youth engagement with the past is also a problem which Philippe Sands mentions in his (2016) book East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Though times and attitudes towards Jewish people in Ukraine have changed since the Second World War, there is still some taboo around speaking of the past, even within families. [10]

Creating an open space for dialogue about these contested histories is something the Centre wishes to achieve, and in doing so they are challenging this stoic approach to national identity – seemingly working towards one which is more open and inclusive. However, whether they also aim to help forge a unified Ukrainian identity through the medium of exhibitions is a matter for debate. The Centre themselves do not claim to do so. Yet within Heritage and Memory Studies, and also Museum Studies, it is often argued that cultural institutions play a part in reflecting and/or building a national identity. [11] [12] To a certain extent, the Urban Centre’s previous photo exhibition entitled “Tomorrow Will Be Better” was a good example of this: a series of photos capturing what everyday Ukrainian life was like between 1989-1991 became very popular with both older generations who lived through that period of dramatic change, and younger generations who wanted to learn more about it. Seemingly this is a period which has become ingrained even in those who were not alive and has become a synonymous part of Ukrainian identity. Drawing people together from different communities is something which the Centre is evidently capable of achieving. Additionally, they have also been very active in supporting the regeneration of Jewish heritage in places such as the Golden Rose Synagogue – promoting minority heritage and including it in the development of the community, even though this admirable effort is currently being met with some vandalism. In this regard organisations like the Urban Centre, regardless of whether they are conscious of it or not, can play a vital role in community-building and understanding the past; they provide space for the contested histories to be deconstructed, thereby creating a better understanding of the self and forging a clearer, more self-critical path into the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there does not yet seem to be one strong Ukrainian identity narrative; the pockets of different communities appear to be living uncomfortably side by side. Through exhibitions such as “[un]named” the Urban Centre is addressing the lack of multicultural unity by showing that unity cannot exist until they come to terms with the injustices done to those minority communities in the past.

Cultural institutions such as museums and places like the Urban Centre are typically seen by academics as reflecting modern society. [13] [14] If that is the case, then to what extent can they represent the entirety of society? The Urban Centre states that they do not represent or reflect society. However, with the cross-generational success of their event “Tomorrow Will Be Better”, they found success because the public were able to resonate personally with the material on display. Their involvement with Jewish-focused projects around Lviv, and “[un]named” also suggests that they are willing to be involved in the strengthening of the heritage of particular minorities, and also play a role in helping the country to come to terms with its more controversial past concerning minorities.

Upon further consideration of Delphine Bechtel’s work, it would not appear that the ideal of one Ukrainian identity is actively being sought. However, parts of society remain caught in a conflict between future and past. On the one hand, there are those who do not wish to reopen the old wounds of the past and would prefer to focus on building on a brighter future for Ukraine. On the other is a community who believes that in order to build a stronger future, you must first acknowledge and embrace the controversies of the past – only then will you have a stronger and more stable future identity. Only when these two sides come to an agreement over how to manage their history, and where minority communities fit into the broader society will there be scope to carve out a strong, unified, Ukrainian national identity.

Footnotes

[1] Bechtel, D. (2011), p.1.

[2] “Our Mission”, Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe [Online].

[3] “Exhibitions”, Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe [Online].

[4] Matsevko, Dr. I. (2017). Personal conversation with Amanda Smith and Nina Verheul during a student field trip to Lviv, 2nd October.

[5] Moser, S. (2010), pp.22-32.

[6] Starovoyt, I. (2017). Personal conversation with Amanda Smith during a student field trip to Lviv, 3rd October.

[7] “Our Mission”, Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe [Online].

[8] Kechur, R. (2017). ‘The Obligation of Ritual’.

[9] Cultural Studies student of the Ukrainian Catholic University (2017). Conversation between students of the Cultural Studies course, and the students of Heritage and Memory Studies from the University of Amsterdam during a student field trip to Lviv, 5th October.

[10] Sands, P. (2016), p. xxx.

[11] Hall, S. (1999), pp.3-13.

[12] McClean, F. (1998), pp.244-252.

[13] Arinze, E.N. (1999), pp.1-4.

[14] De Clerq, S. (2003), pp.57-65.

Bibliography

Arinze, E.N. (1999). ‘The Role of the Museum in Society’. Public lecture at the National Museum, Georgetown, Guyana (17th May), pp.1-4.

Bechtel, D. (2011). ‘Ukrainian Lviv since 1991 – a City of Selective Memories’ found at European Network Remembrance and Solidarity [Online], pp.1-3. Available at: <http://enrs.eu/articles/97:ukrainian-lviv-since-1991>. [Accessed 30th July 2017].

De Clerq, S. (2003). ‘Museums as a Mirror of Society: A Darwinian Look at the Development of Museums and Collections of Science’. Conference paper delivered at UMAC 2003, pp.57-65.

Hall, S. (1999). ‘Whose Heritage? Unsettling “The Heritage”. Re-imagining the Post-nation’ in Third Text 49, pp.3-13.

McClean, F. (1998). ‘Museums and the Construction of National Identity: A Review’ in International Journal of Heritage Studies 3(4), pp.244-252.

Moser, S. (2010). ‘The Devil is in the Detail: Museum Displays and the Creation of Knowledge’ in Museum Anthropology 33 (1), pp.22-32.

Sands, P. (2016). ‘Prologue’ in East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, p. xxi-xxx.

Additional Material

Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe [Online]. Found at <www.lvivcenter.org>. [Accessed 25th October 2017].

Cultural Studies student of the Ukrainian Catholic University (2017). Conversation between students of the Cultural Studies course, and the students of Heritage and Memory Studies from the University of Amsterdam during a student field trip to Lviv, 5th October.

Matsevko, Dr. I. (2017). Personal conversation with Amanda Smith and Nina Verheul during a student field trip to Lviv, 2nd October.

Kechur, R. (2017). ‘The Obligation of Ritual’. Supplementary text to the “[un]named” exhibition (2017).

Starovoyt, I. (2017). Personal conversation with Amanda Smith during a student field trip to Lviv, 3rd October.