A visual culture, a visual conference

On May 7th during the Human Rights Nights film festival for which I have been working these first months of 2018, we helt something we have called a visual conference. This meant that instead of taking a proposition to be debated, we presented a collage of moving images from the news and other sources to open-up and provoke discussion among the various panels. We thought of this as much more suited for a film festival. With a group of master students of the Università di Bologna who followed a course in visual anthropology, we brainstormed about how the clips could achieve this effect. They should — we thought — tackle or intersect with contemporary debates, or showcase a certain tension present in the perception produced by the media. So, I asked myself, what could be the advantage to choose for a visual conference over a regular one? Here are some meditations.

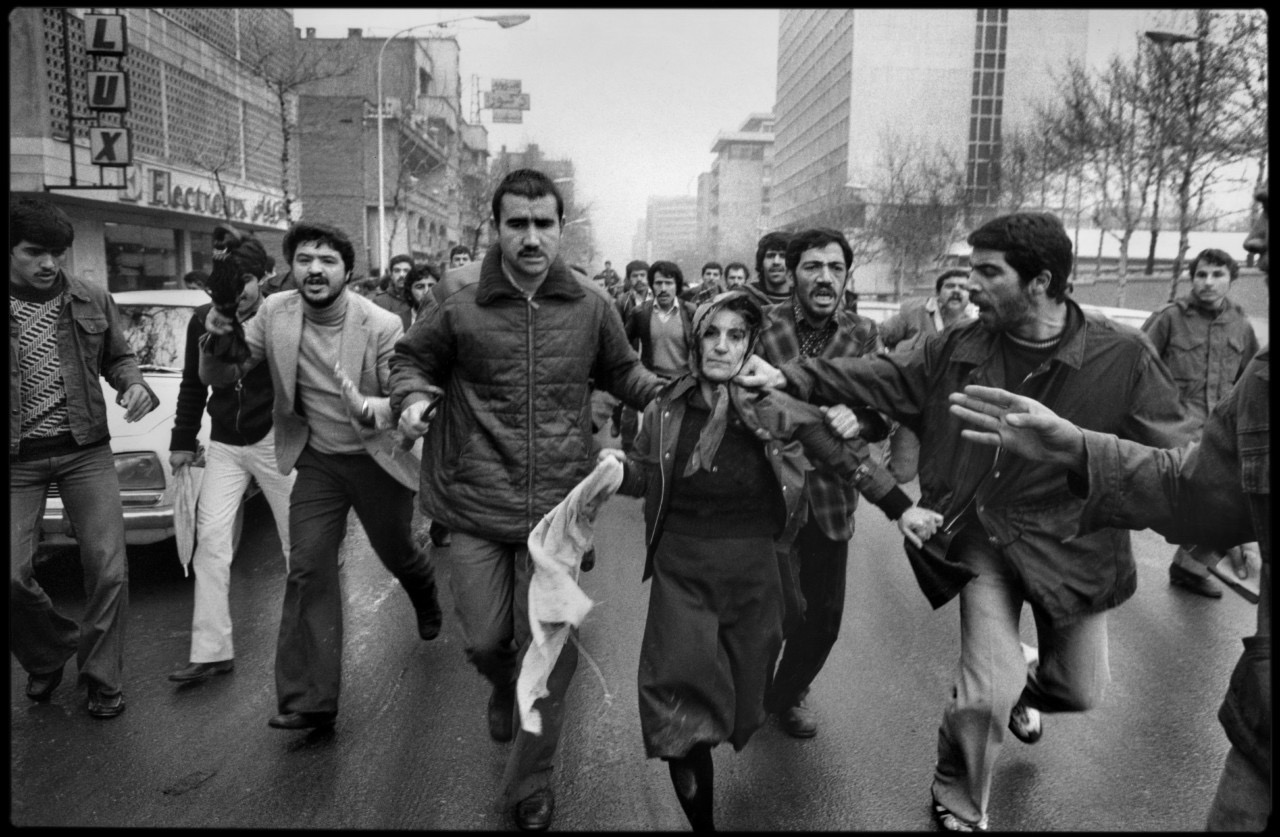

Since the development of photography, television, and the internet, an increasingly global visual culture has emerged as opposed to one that is dominantly spoken or written. News is accompanied by images to attract attention or to support its content. Events thereby become perceived more intimately. Think about the weight the pictures taken by Robert Capa of the Spanish Civil War carried, or how Abbas’ camera brought the the Iranian Revolution closer to us. Remarkably as well is the high-speed rhythm in which these images could be produced and consumed — something previously incomprehensible. The way images are perceived had also a lot to do with my studies in semiotics at the Università di Bologna in which the analysis of media and its performative effects are at center stage. Hence my studies and internship started to overlap, giving me an opportunity to “put the theory into practice” — so to say.

Each edition of the Human Rights Nights film festival has a theme that tries to reflect the times through its choice of films and documentaries. The theme we had chosen for this 18th edition and therefore also for the visual conference was dis-integrazione – or in English ‘dis-integration’. We interpreted and thus divided this word into five separate, though interrelated meanings: the disintegration of the body politic (or at least the populist rhetoric as such) — think about the etch in Hobbes’ Leviathan here; the disintegration of previously broadly shared values, such as human rights; the disintegration of human bodies and cities due to war and the fleeing from it — p.e. Syria; the disintegration of the planet through climate change; and last but not least ‘integration’ and the charged political discourse around it. Summed up they fleshed out the meaning of the word as it is in the dictionary and it’s contemporary connotations. In other words, disintegration can be understood as the reverse movement of integration, in which bodies, biological and/or political, merge together to form a new whole.

Robert Capa. Death of a loyalist militia man at the Cordoba front, Spain. 1936. The soldier depicted got shot in the same moment as he got ‘shot’ by the photographer himself. Copyright: International Center of Photography| Magnum Photo’s.

Robert Capa. Death of a loyalist militia man at the Cordoba front, Spain. 1936. The soldier depicted got shot in the same moment as he got ‘shot’ by the photographer himself. Copyright: International Center of Photography| Magnum Photo’s.

Attar Abbas. Teheran, Iran. 1979. After a demonstration a woman believed to be a supporter of the Shah is mobbed by a revolutionary crowd. Copyright: Abbas|Magnum Photo’s.

Attar Abbas. Teheran, Iran. 1979. After a demonstration a woman believed to be a supporter of the Shah is mobbed by a revolutionary crowd. Copyright: Abbas|Magnum Photo’s.

“If it bleeds, it leads”

Those two things — the high rhythm of images and bits of information in which today’s visual culture seems sometimes to drown rather than to swim, and the ever-present conflict in the world, its proper disintegration — also form the focal point of Susan Sontag’s essay Regarding The Pain Of Others (2003). There Sontag writes: ‘Wars are now also living room sights and sounds. Information about what is happening elsewhere, called “news,” features conflict and violence — “If it bleeds, it leads” runs the venerable guideline of tabloids and twenty-four-hour headline news shows — to which the response is compassion, or indignation, or titillation, or approval, as each misery heaves into view.’ Although Sontag might sound a little cynical here, she reveals a dimension of modern mass media culture that seems to me has not lost importance today. Quite the contrary.

The visual culture she aims at seems to be strongly bound up to the political stirring up of underbelly emotions and more banally, making profits (“a great deal!”). Sensational news deploying hyperboles and a shock effect — “War on terror”, a “Clash of Civilizations” — however have long-term effects on people’s imagination and perception of the world outside. For example, his type of information-nudging can legitimate violence. The word “war” is often employed perform this. The word war is namely imagined as a consent to a balanced fight between two parties using armed violence, while that is very often the case and also bypasses a conflict’s complexity. It also distracts people from what is truly going on: the facts, so to say. In this move, it quietly Others: it presents us with a static self-image (the liberal west!) and a static antagonist of the other (the invader!). For the reason of understanding how the imagination is played at and shaped by these omnipresent (moving) images, a visual conference is I think therefore suited for the job.

Nilüfer Demir. Turkey. 2015. Syrian-Kurdish kid Aylan Kurdi, stranded on the beaches of the Mediterranean. The way this image travelled through the world, tells us what is necessary to achieve a shock effect in visual culture.

Triumphal Ode

We presented a selection of clips out of the tons that could be found online and that each daily ask for our attention and reaction, generating clicks (read: cash). They had to be representable for what can be found online, but instead of watching it personally on a laptop or smart phone screen, while receiving a dozen messages, they were presented on the big screen to carefully analyzed. Contrary to the logic of the shock-effect, these clips could therefore be properly reflected on. Instead of in the modern rhythm of the projector — r-r-r-r-r-r-r — as the machines in Álvaro de Campos, one of Fernando Pessoa’s alter ego’s, poem Triumphal Ode (1914) go, they could be taken apart and assembled into a bigger picture. I believe that can contribute to our understanding of how conflict is perceived in our present visual culture. De Campos Triumphal Ode is simultaneously celebrating and loving as well as criticizing modern mass culture. Its metric, its rhythm, and its content intermingle in such a way that can only be an apt description of the modern vertigo Pessoa’s contemporaries were faced with on the eve of the Great War:

“Contradictory notices in the journals,

Political articles insincerely sincere,

News passez á-la-caisse, inordinate crimes —

Two columns of it continued on page two!

Fresh smell of typographic ink!

Newly hung posters, wet!

[…]

O merchandise in the showcases! O mannequins! O latest models!

O useless articles everyone wants to buy!

Olá great department stores!

O neon advertisement appearing one after another, only to disappear!

Olá everything with which today that constructs itself, with which today becomes different from yesterday!

Eh, reinforced concrete, cement mixer, new processes!

Progress of glorious deadly armaments!

Armor, cannons, machine-guns, submarines, air-planes!

I love you, all and everything like a beast.

[…]

Hé-la great rail disasters!

Hé-la collapsing mine-shafts! Hé-la delicious shipwrecks of the great transatlantics!

Hé-la-ho revolutions here, there, all over everywhere,

Alterations in the constitution, wars,treaties, invasions,

Noise, injustice, violence, and maybe soon to come,

A great invasion of yellow barbarians into Europe,

And another Sun on a new Horzion!

What does it matter, but what does all this matter

In the fulgent blood-red contemporaneous noise,

The cruel and delicious noise of today’s civilization?

Everything obliterated except the Moment,

The Moment with the hot nude torso and a stoker,

The stridently noisy and mechanical Moment,

The dynamic Moment passing through every bacchant

Of iron and bronze in a drunken spree of metals.”

Reading the poem in our present-day mass mediated culture, we cannot help feel at once alienated and all too contemporary to Pessoa. This vertigo has perhaps become mere habit, a repetition for us in the continuous present. A final strophe by his Álvaro de Campos:

“I sing, and sing in the present, also in the past and the future

Because the present is all the past and all the future”

References

De Campos, Álvaro. (1914). Triumphal Ode or Ode Triunfal.

Sontag, Susan. (2003) Regarding The Pain Of Others. New York: Picador.

Front Picture

Brothers Lumière. L’arrivée d’un train a La Ciotat. 1895. Stil.