Remembering and forgetting of a multi-layered past for the construction of an Ukrainian national identity

by Sanne Letschert

Leopolis, Lemberg, Lwów, Lvov and Lviv: five different names for the same city. To a great extent each name reflects the different periods of the city’s turbulent history and the different political entities that have made it their ‘own’. The city of Lviv, located in the historic province of Eastern Galicia in Ukraine, has been marked by these subsequent conquests and is very much a product of this historical process. With every change of rule, the urban landscape of the city changed as well. The style of architecture, names of streets and squares, cemeteries, monuments and museums were all adjusted to fit the city’s new identity. In the material presence of the city, traces of this multi-layered and cultural diverse past remain visible everywhere: Lviv is an urban palimpsest. During this excursion it was my objective to discover these different layers of the past in the public spaces of the city and to analyse what story they tell us.

On this page you find my research results of and reflections on our visit to the city of Lviv in Western Ukraine. In the podcast episode below you can listen to the most important elements of my preliminary research into the multi-layered past of the city and some interesting features of my presentation on the analysis of Prospekt Svobody, or Freedom Avenue, one of the most central spaces of the historic centre of the city and my case study for this research. After the podcast you can read deeper into the result of my research and my ideas on the story of the layer that is most visible in the urban space of the city today.

Discovering the Layers of Lviv

This podcast episode on ‘Discovering the Layers of Lviv’ will be a brief introduction into the history of the city, the objectives of my research and the results of my analysis of the traces of history on Prospekt Svobody, or Freedom Avenue. The episode will give you some examples of how those layers are visible in the architecture, statues and monuments of the city. It will also give an insight in how Western Ukraine and Lviv became the centre of Ukrainian nationalism and the important role the city has played in the construction of the Ukrainian national identity after the country became independent in 1991.

Remembering, Forgetting and an Ukrainian Identity

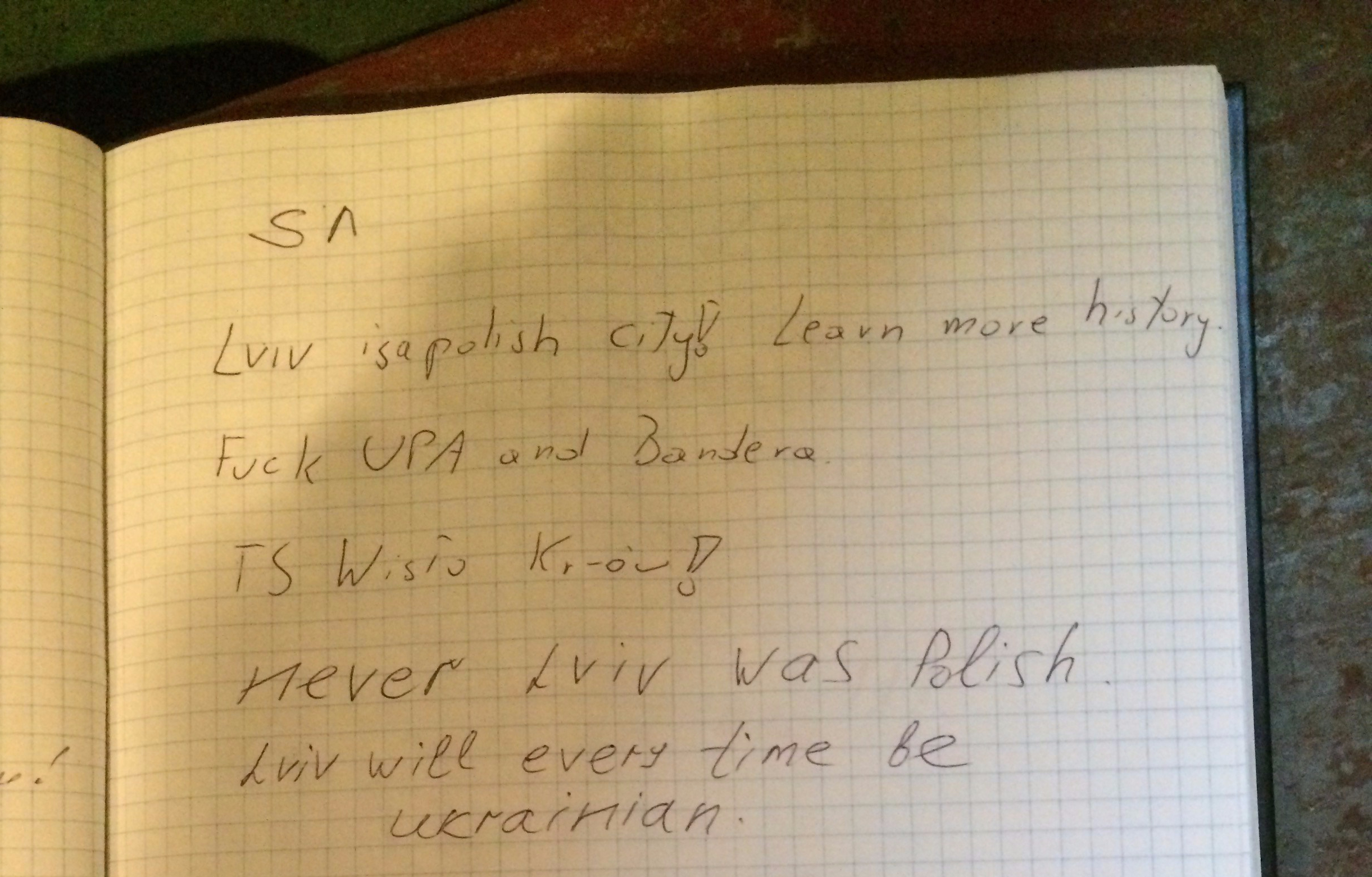

Researching the visibility of the different layers of Lviv’s past and the site analysis of the public space of Prospekt Svobody have led to the conclusion that one layer is definitely most visible in the city scape today: the Ukrainian past and present. This goes not only for one the most central spaces of the city, but is also evident in the rest of the historic centre. The urban signage is like an Ukrainian national pantheon and numerous monuments and statues glorify Ukrainian national heroes – both replacing those markers that remind of a Habsburg, Polish, Jewish or Soviet past. A selective remembering and forgetting of the past and a selective representation of the multicultural heritage of the city have led to what the city looks like today: a Ukrainian, somewhat Western-oriented city, that pays little to no attention to the multicultural and diverse legacy of its multi-layered past. On the other hand, there are elements in the city that seem to indicate that this might be, slowly, changing.

As mentioned in the podcast, it is important to be aware of the historical processes of the region and the position Lviv and Western Ukraine were in after the fall of the Soviet Union and the Ukrainian independence in 1991. Crucial was the major change of population in the 1940s, when Lviv lost around eighty-five percent of its original inhabitants because of Ukrainian-Polish ethnic violence, the Nazi Holocaust, Soviet resettlements of Poles and deportations of Ukrainians convicted for their resistance against the Soviet regime. They were replaced by people from the countryside of both Western and Eastern Ukraine and by Russians from elsewhere in the Soviet Union (Hrytsak, Susak 2003:150). This severely disrupted the transmission of the collective memory of the different cultural and social groups and the heritage of the city. Without this ‘communicative memory’ the new inhabitants of the city had yet to develop a connection with the history and heritage of Lviv (Assmann 2008: 109-118). Therefore the post-war period in which Lviv was part of the Soviet Union was also vital for the development of the city, when it was transformed into an Ukrainian Soviet city. This actually fed into Ukrainian nationalism, which was roaring in last years of the Soviet Union building up towards Ukraine’s independence in 1991. In this period the country had to develop the Post-Soviet identity of an independent Ukraine. Lviv, as part of the region of Galicia, was reinvented by intellectuals as the historic and ‘rebellious’ cradle of Ukrainian identity and the city became crucial for the Ukrainian nationalistic discourse. This led to a ‘Ukrainization’ of the public spaces of Lviv, representing this strong, national and regional identity (Hentosh, Tscherkes 2009: 257).

To a great extent, the result of the decommunalization and the post-Soviet Ukrainian identity building is what the city looks like today. As analysed in the case study of Prospekt Svobody, street names were altered and there was a change of the bronze guard in the central spaces of the city. For example, the statue of the famous Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko replaced the statue of Lenin, symbolically leading the wave of national renewal. Because of its nineteenth century architecture, squares and avenues (legacy of the Habsburgs), Lviv never feels completely Ukrainian and always reminds of the cities of East Central Europe, like Vienna.

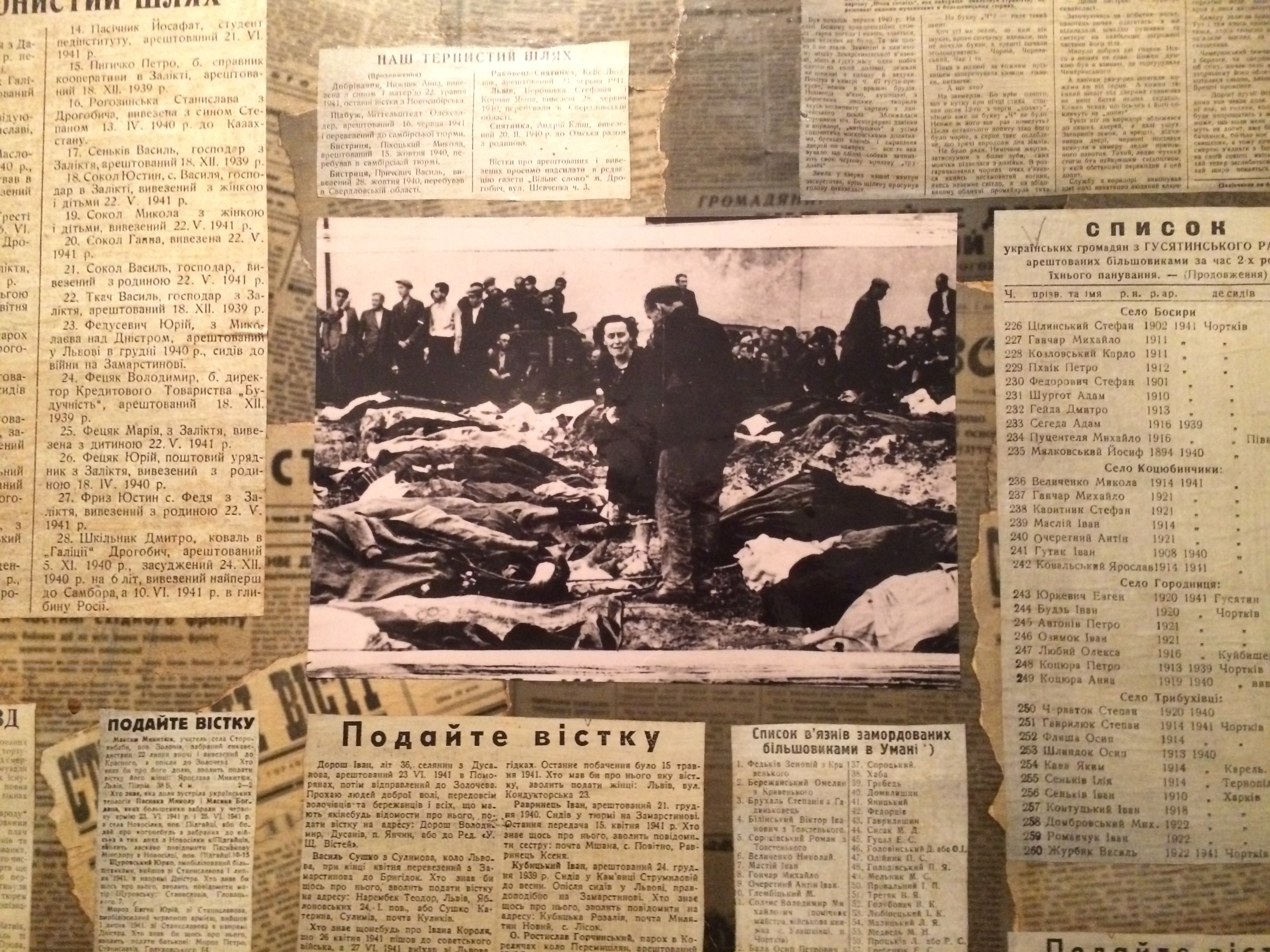

However, the other semiotics of the city scape most definitely emphasize the Ukrainian identity of Lviv. This is also visible in for example the musealized Lontski Prison, on Stephan Bandera Street (also an example of a street named after a national ‘hero’). The prison holds the stories of all phases of the twentieth century history of Lviv: the prison was built in the nineteenth century by the Habsburger gendarmerie and continued to serve this purpose during Polish times. When Lviv capitulated to the Red Army in 1939 the prison was initially used to imprison rebellious Polish citizens, but after 1940, when the Ukrainian resistance against the Soviets increased, the prison was used more and more to lock up Ukrainian patriots. This ended in a bloodbath when Germany occupied the city in 1941, in which hundreds of Ukrainian prisoners were killed. Under the German occupation Lontski served as Gestapo prison in which Jews and citizens trying to help them were imprisoned. In the Soviet Era the building became a KGB prison and was the notorious gateway to the Gulags. After Ukraine’s independence in 1991 the Security Service of Ukraine takes control of the prison (Driebergen 2014: 44-48). Those layers of history are briefly mentioned in the English text hand-out (the texts on the walls were in Ukrainian), but the emphasis in the narrative of the museum is very clearly on the Ukrainian patriots that were imprisoned here, their battle for independent Ukraine, the mass killing that took place and on the injustice that has been done to the Ukrainians and other prisoners during the time when it served was a KGB prison of the Soviets. So we could say that the desire to break with the Soviet past erased all Soviet traces from the public spaces of the city, but in the quest for finding a new national identity all other traces of the multicultural history of Lviv were alien, not fitting, and therefore neglected and ‘forgotten’ in making the public spaces of Lviv Ukrainian.

Towards change?

On the one hand the strong Ukrainian identity is still noticeable in the city, not least because the theme of one of the most popular restaurants in the city is still celebrating the patriotic Ukrainian resistance against the Russians after the Second World War under the slogan ‘the battle goes on’ (which inevitably makes you think about the ongoing conflict in the East of the country). But on the other hand I have also noticed change. Listening to the other presentations of our group, visiting some of the most important places and talking to Lvivians, I have noticed an openness to discuss the other, sometimes dissonant, multicultural histories of the city. Also in the public spaces you can notice this slow movement towards this direction. The recently unveiled monument of the Golden Rose Synagogue for example, paying respect to the memory of the numerous Jewish citizens of the city that became victims of the Holocaust (you can read more about this on the page of Nazlu and Martina), or the rebuilding of the pantheon of the Polish soldiers on the famous Lychakiv Cemetery in 2005 (read more about this cemetery on the page of Paige), or, my personal favorite, the uncovering and sometimes even restoration of old painted Yiddish, Polish and German shop signs remembering of other former citizens of the city. All these changes seem to be referring to a different way of treating the past and are again influencing the public space and the way the city looks today. This could indicate a different attitude towards the complicated, multicultural legacy of the city.

This made me wonder what is important for the people today. With the Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Euromaidan demonstrations in 2014 in mind, it seems to me that Ukraine is still very much reinventing its national narrative and identity. Not only regarding its attitude towards Western Europe and the European Union, but also in respect to the discrepancy between the West and the East of the country itself. The changes in the city of Lviv might very well be influenced by these events in recent history. By recognizing the multicultural aspects of its history more, by officially remembering the victims of the Holocaust and by emphasizing the Central European character of the city, Lviv seems to be trying to approach the European frame of memory politics and to stress its European ‘belonging’. This is something that is probably at odds with the attitude of the Eastern parts of the country, which contributes to the tensions between the East and the West. What might also evoke the changes is the fact that the younger generation of Lvivians seems to no longer be able to identify themselves with the fabrications of the early nineties and the Ukrainian nationalist heroes decorating the streets and squares of the city. During our visit to the Catholic University we were talking to students of the bachelor Cultural Studies and it seemed to me that they were all struggling to decide to what Ukraine they (want to) belong and that their opinions about what Ukraine represents are very different. After our joint conversation in class I was looking at a portrait of a student who died during the protests of Euromaidan that was hanging in the hallway of the university. One of the students came up to me and told me that many of them see the victims of Euromaidan as the heroes of a modern Ukraine. He also told me that at the time thousands of Lvivians had been protesting on Prospekt Svobody.

With Prospekt Svobody I am back at the place in the city where I started. Even in recent history the public spaces of the city are appropriated to become part of a specific story. The reconsideration of the multi-layered past of Lviv seems to be still going on and continues to influence the appearance of the city. A visit of six days was nowhere near long enough to fully understand the complex process of remembering and forgetting in the construction of the national Ukrainian identity and the regional identity of the city of Lviv, which still seems to be going on today, and the role urban spaces play in this. To understand better the dynamics between these two, especially regarding the attitude towards Western Europe, Russia and the recent events, it would be good to travel further eastwards to see what stories the cities can tell us there.

Assmann, J., ‘Communicative and Cultural Memory’. In: Cultural Memory Studies. An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Erll, A., Nünning, H., Berlin: de Gruyter (2008), pp. 109-118.

Hentosh, L., Tscherkes, B., ‘Lviv in Search of its Identity: Transformations of the City’s Public Space’. In: Cities after the Fall of Communism: Reshaping Cultural Landscapes and European Identity, edited by Czaplicka, J., Gelazis, N., Ruble, B., Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (2009).

Hrytsak, Susak, ‘Constructing a National City: the Case of Lviv’. In: Composing Urban History and the Constitution of Civic Identities, edited by Czaplicka, J., Ruble, B., Washington: Woodrow Wilson Center Press (2003).

Kesseler, D., Driebergen, M., Ruyven, van K., et al, Lviv: Stad van Paradoxen, Oentsjerk: Mauritsheech (2014).