By its very nature, heritage is an emotive subject. The very existence of heritage relies on the fact that certain sites, objects or ideas are particularly evocative of the most deeply-held values and belief systems of a particular community, usually through their association with a seminal historical event that shaped how that community currently lives. The problem is, the same site or object may evoke very different values and beliefs among different communities, or even within the same one. This is the result of different groups interpreting the site or object in very different ways, as a result of each having a different narrative for the historical events that surround it. This is most often referred to as ‘contested heritage’, and it will be the primary theme of this episode.

Sofia Lovegrove and Simon Taylor both focused on sites directly related to one of the most controversial periods of Trieste/Trst’s history: the Nazi occupation during the Second World War, and the influx of immigrants from Yugoslavia as a result of the rise of communism that immediately followed. Simon discusses how his site, the Risiera di San Sabba, is a battlefield in an ongoing fight for victimhood status between those who want it preserved as a Holocaust site representative of the evils of Fascism and Nazism and those who want to see it remembered as the refugee camp that it later served as, representing the evils of communism and the associated Foibe Massacres that took place during that time. Sofia meanwhile discusses the virtual non-existence of her historical site, a former refugee camp known as the ‘Silos’, and uses that example to explain the many controversies that have arisen over representing the ‘Exodus’ of Italian Istrians from Yugoslavia, the largest and most vocal group of the exiles. Both case studies reveal sharp divisions in terms of politics, ethnicity and the general understanding of history.

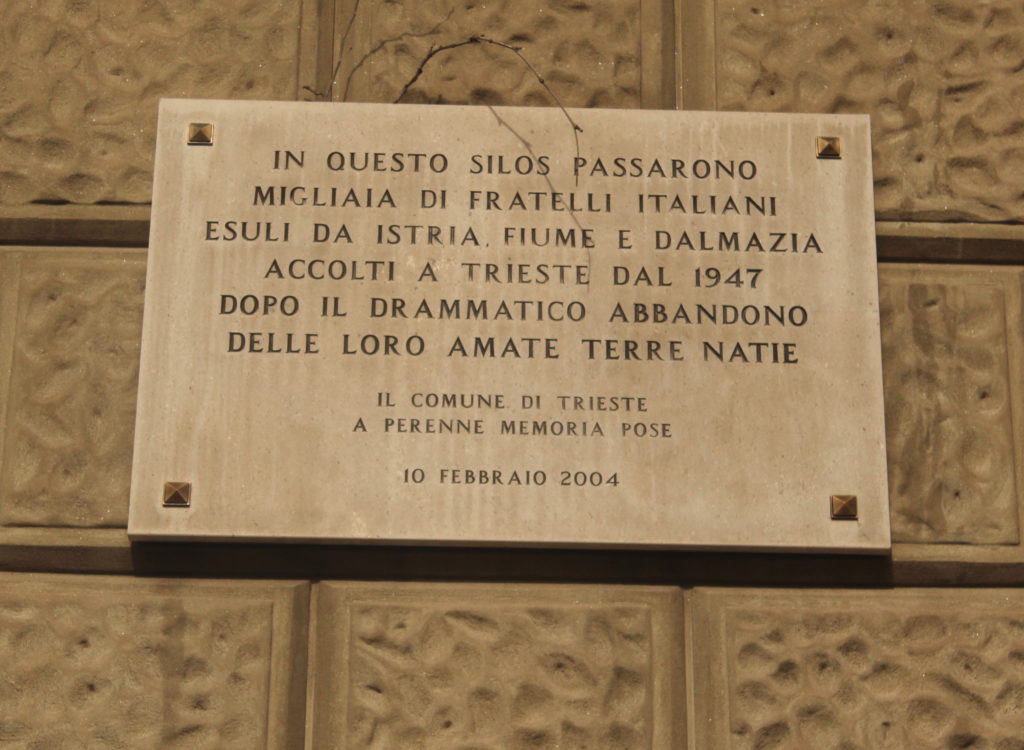

Sofia Lovegrove focused her research on the ‘Silos’ building, located near the Piazza della Libertà. According to the limited information available, the Silos was built as a grain depot in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Trieste/Trst was part of the Habsburg Empire. Following the Second World War, and especially after the Paris Peace Treaty (1947), the Silos was used as a refugee camp, in the context of the so-called ‘Exodus’. In this region, the term refers to the several mass population movements in the 1940s and 1950s of people from the regions of Istria and Dalmatia into Italy; people who considered themselves ethnic Italians, fleeing as a result of the border disputes with former Yugoslavia and the changes that characterised the postwar period. The Silos was used as a refugee camp for these Italian refugees of the Exodus (amongst people of other nationalities), for an uncertain period of time. Many of these Italian refugees refer to themselves as ‘esuli‘ or exiles, in reference to the Exodus.

As Pamela Ballinger explains in History in Exile (2003), the Second World War and the Exodus dominate Trieste/Trst’s memoryscapes today, and constitute the location of many politically charged discussions. The memory of the Exodus that has been shaped by the exile communities and related associations is particularly cultivated by (far) right-wing politics, partly as a way of fomenting nationalist sentiment. The Silos plays a very limited role in these discussions, despite earlier (unsuccessful) efforts of the Unione degli Istriani to carry out research about the site. Other, more visible and ‘authorised’ sites of memory of the Exodus include the Monument to the Exodus and the Day of Remembrance of the Foibe and the Exodus. During her research, Sofia looked at the Silos in the context of Trieste/Trst’s broader memoryscapes concerning the Exodus, and she explored the role that the exile narrative plays in the city today.

The Risiera di San Sabba was, as its name suggests, originally built as a rice-husking facility. Although the site was established as a mill in 1893, most of what can be seen of it today did not go up until 1913. The mill continued to be used for its intended purpose for the next three decades, enduring the First World War, as well as the rise and original deposing of Mussolini and his Fascist Republic. However, when Nazi Germany re-installed Mussolini as dictator and set up the Republic of Salò as a puppet state, the Risiera di San Sabba was turned into a ‘Polizeihaftlager’, or police concentration camp. Gas chambers and crematoriums were installed at the site, the latter designed by Erwin Lambert, one of the most notorious architects of the Holocaust. Around 3000 prisoners are believed to have been killed there, and countless more sent to die at other camps such as Auschwitz.

In 1945, as allied forces came ever closer, the Nazi forces purposefully bombed the site as a means of destroying any evidence of genocide. No-one directly responsible for running the Risiera di San Sabba concentration camp was ever successfully prosecuted.

Almost immediately after the war ended, the rise of communism in Yugoslavia under the dictatorial regime of Marshal Tito meant that many ‘ethnic Italians’ (usually Istrians) who lived close to the border fled into Italy, meaning that the Risiera di San Sabba was again called into use, this time as a displaced persons camp. Throughout the late 1940s and most of the 1950s, it acted as one of the original points of refuge for those fleeing communism.

In 1965 the site was declared a national monument, and was made into a museum a decade later. The museum is dedicated solely to the Risiera di San Sabba’s role as a Holocaust site, with almost no mention of its later role as a place of refuge for displaced persons. However, Istrian advocates and Italian nationalists have long called for the site to memorialise those who were forced to flee Yugoslavia, as well as those Istrians who were killed in the associated Foibe Massacres. As Simon Taylor found out, the debate surrounding the San Sabba continues to rage on, reflecting much deeper divides within Trieste/Trst.