By Jelmer Peter & Bram de Jong

This part of the website is about our excursion to Janowska concentration camp and a site analysis on this particular campsite (as an addendum to the podcast). We decided to include in our writings the other camp we visited, at Trawniki, Poland, because to our research Trawniki was a premise to Janowska; without the former we would not have encountered the latter. What follows is a chronological story that begins with Trawniki and ends with the main project: Janowska concentration camp.

Podcast Janowska Campsite

Research developments

When reading Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands (2010) we became acquainted with the history of the Trawniki men. This group, for the largest part Soviet POW’s who were trained by the SS in the Trawniki camp near Lublin, had to guard and manage the death factories from Aktion Reinhard (Black, 2011, 5). Whilst reading articles on Trawniki and the Trawniki men, our lecturers advised us “to include the former concentration camp Janowska in Lviv in our project, because in 1942 a notorious detachment of Trawniki men was sent to guard and control the Janowska camp”. The Trawniki men were often hesitant about the tasks they had to perform, sometimes leading to desertion. It is one of the reasons why the Nazi’s often perceived them as untrustworthy. In that respect a theory to incorporate into the research was for example the intentionalist-functionalist debate that originated from Daniel Goldhagen’s critique in 1996 on Christopher Browning’s Ordinary men (1992). The debate is crucial when problematising the layers of perpetratorship since the motives of Trawniki men are unclear still. This can be deduced from the situation in which the men were recruited: the German POW camps were brutal environments one would like to escape in any way possible. Furthermore the many stories of desertion and suicides show the unwillingness of the Trawniki men to perform their job (Rich, 2014, 271-272).

The initial aim of our research in Ukraine and Poland was to lay bare the multifaceted nature of ‘diffuse perpetratorship’. During our visits to the camps we wanted to invite our fellow students to constantly revisit the question of ‘how the involvement of the Trawniki men in the Final Solution is formulated in the respective camps’. We wanted to show that the Trawniki men are good examples of diffuse perpetratorship, meaning they cannot be placed in one all-encompassing category of perpetrator. In addition, the Nazi’s recruited approximately 5000 men from different (Soviet) nationalities, of which the dominant group was Ukrainian (Black, 2011, 6-7). The ideologies and motives of these men (and one woman), we supposed, need specification, sometimes all the way down to the individual level, in order for a more nuanced view to appear. Furthermore we wanted to find out how local guides, and significant landmarks at the site itself are telling the story of Trawniki men in both Trawniki and Janowska. It can very well be that academic literature on the subject has progressed miles ahead (in thought) and the actual object is not presented according to the newest insights. In consequent the story that is told on site can be perceived ignorant or worse: it can be provoking.

Eventually the end product of the project changed into a podcast on the Janowska campsite with a remark of the Trawniki men rather than the other way around. At Janowska we were startled by the appropriation of the space of the people of Lviv and consequently the different ethical considerations that follow when, for example, part of a concentration camp is used to build a new neighbourhood on. At Trawniki we encountered a similar situation where parts were reused or replaced, sometimes without proper documentation of the camp’s remains: the mass execution sites at Trawniki were partly covered by new houses, which raises the question whether this action was appropriate or that the present memorial is enough – enough for whom though? To grasp the wrong- or rightness of spatial ethics the researcher should include practicalities such as urban agglomeration, combined with ignorance and failing legislature when excavating and observing historical sites.

Site Analysis: Janowska, the forgotten concentration camp of Lviv

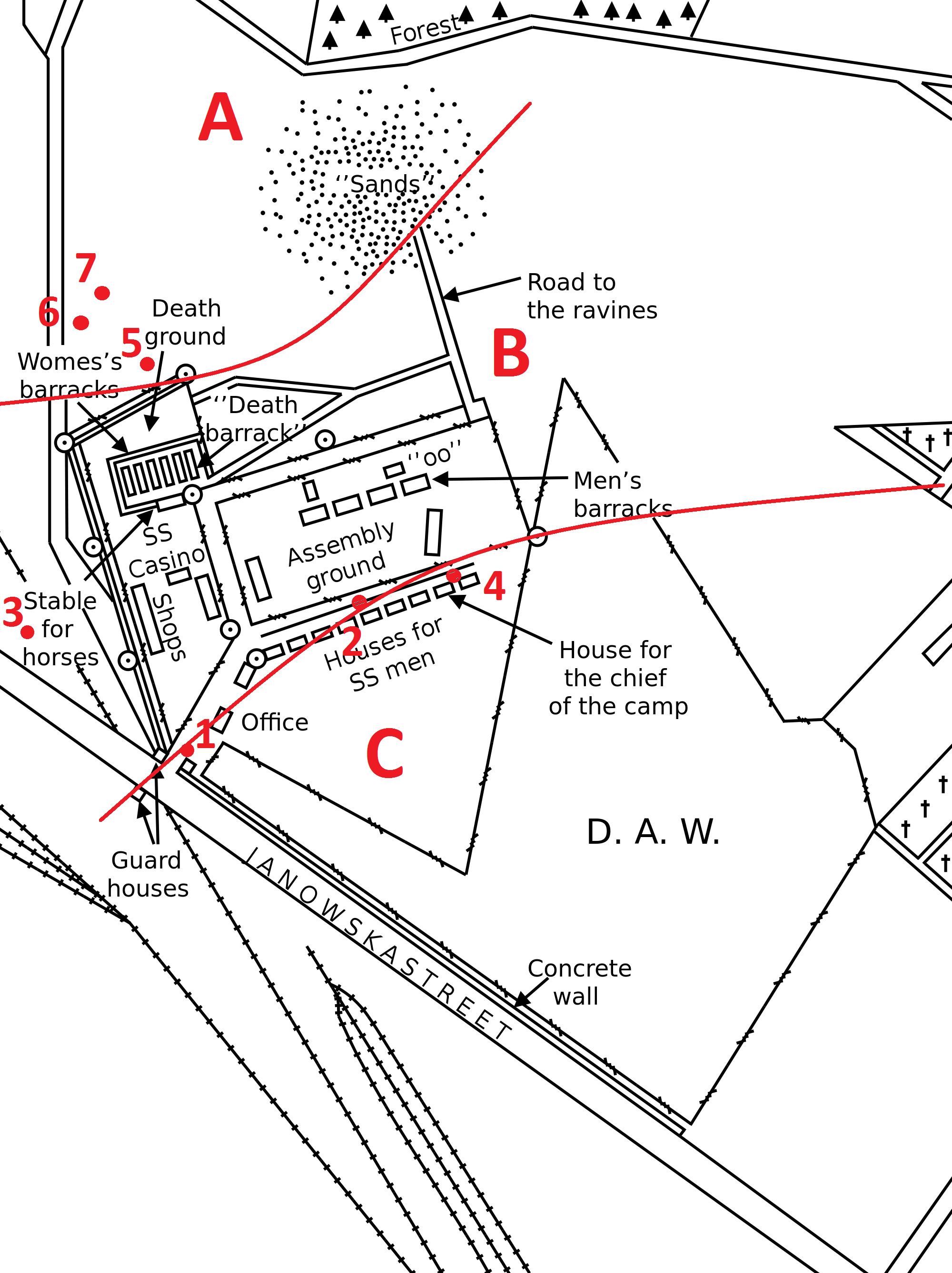

This short site analysis concerns the forgotten Nazi concentration camp at Janowska Street in Lvív, Northwestern Ukraine. Janowska concentration camp was active as a forced labour camp from 1941 until late 1943. In that period an estimated 40.000 Jews were shot at Janowska. At least another 100.000 Jews passed through Janowska to the extermination camp at Belzec, where they were gassed immediately upon arrival. Janowska played a crucial role in the extermination of Jewry in South-Eastern Galicia. A significant site of the Holocaust, however today Janowska bears little trace of its traumatic past. After the Second World War the buildings in the middle part (see map) were reused by the Soviets as a prison, and today the buildings are still used as a prison. The German army factory (Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke, DAW) on the south-eastern grounds, is, as abovementioned, demolished and the terrain is recently transformed into a residential area with new buildings. Finally, the ‘death grounds’ – the site where some 40.000 Jews were executed – are not in use and have a remembrance stone and signs near the entrance. Other than that, no commemorative practices or attempts of preserving the site are undertaken. The former Nazi concentration camp at Janowska street attests of the fact that Ukrainian collective memory of the Second World War is not primarily preoccupied with commemoration of the Holocaust. In this brief site analysis we will elaborate on the absence of holocaust narratives at Lviv’s forgotten Nazi camp.

There is an absence in awareness of the significance, even the existence, of the Janowska concentration camp amongst inhabitants of Lviv. First, the camp is not preserved as is the case with concentration camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau or Majdanek, that have become musealized spaces. Secondly, is the limited accessibility due transformation of the former concentration camp into a prison today. Thirdly, the street on which the camp is situated is renamed from Janowska to Omeliana Kovcha street. Because the name ‘Janowska’ is no longer in use, not many people are familiar with the location of the former camp. However it is not only a public unawareness of a forgotten place which we are dealing with. On the other hand on site barely any attempts have been made to remember the history of Janowska. The commemoration stone and two signs that mark the site as a ‘site of memory of the Holocaust’ were erected as part of local initiatives from families of the victims (the stone, with explanatory sign) and as part of an international remembrance alliance (the other sign). These markers attest of an attempt to create a narrative at Janowska camp, however they remain the only attempt. Finally, it is not easy to visit the stone and signs with the only path leading to it runs along a busy road without any demarcation signs. The death ground are in a leafy area in close vicinity to the commemoration stone. An apple orchard is bordering the western border of the death grounds. This is another sign that, over the years, the area that covers the death grounds has become part of an increasingly urbanized part of Lviv. How should Lviv deal with its forgotten Nazi camp now that it has become integrated in the urban landscape?

We would argue that the absence of narratives at Janowska makes an exemplary case study for the way in which Ukrainian collective memory of the Second World War does not coalesce with the ‘founding holocaust myth’ that is put forward by the EU. In its strive towards a cultural Europeanisation, the EU tirelessly attempts to institutionalize the holocaust as a ‘ founding myth’ for European identity. However this effort to homogenize Europe’s collective memory of the Second World War, encounters resistance in Ukraine. Ukrainian collective memory is predominantly shaped by the struggle for independence against the Soviet Union. In 1932-33 the Ukrainian Famine took place, under Soviet policies of collectivization. During this so-called ‘Holodomor’ some 2 to 3 million Ukrainians died of starvation. This trauma is as foundational for the national identity of Ukraine, as the holocaust is for the EU’s effort to culturally homogenize Europe. Ukraine is not part of the European Union, and also not a member of the IHRA. However, with Ukraine’s long standing wish to enter the European Union, can we expect a more receptive attitude towards the memory of the holocaust? In a country that is internally divided between the supporters of the EU and Russia, will there be a reconciliation between Holodomor and Holocaust narratives (and what about the Russian perspectives on both events)? Finally, will this result in a more coherently shaped way of commemoration that will do just to the victims of Nazi genocide at Janowska, the forgotten concentration camp of Lviv?

Then, can we expect all former trauma sites of the Holocaust in Europe to be preserved? During our excursion in Poland and Ukraine we have seen a variety of former camps, each commemorated differently. In Janowska, Belzec, Trawniki and Majdanek different preservation methods are present. From the musealized and memorialized spaces at Belzec and Majdanek, to the sites of Trawniki and Janowska where little traces of the past are present; each site has obtained a specific way of dealing with its past. In the case of Janowska, it may be that bottom-up initiatives will result in an increase in public interest in its past. However, several local attempts to increase awareness, initiated by the Jewish community and the Center of Urban History of East Central Europe in Lviv, remain unsuccessful due to a lack of resources.

Images and map

The image below represents a map of the Janowska concentration camp during the Nazi period (1941-1943). the dots resemble the exact location from which the previous photo’s are taken. The numbers (1,2,3,4,5,6,7) correspond to the images above. The letters correspond to the different uses of the area today: A) the abandoned hills where the death grounds are located, B) the Janowska prison, and C) the residential area.

Assmann, A., Conrad, S. (eds.) (2010). Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Karlsson, K-G. The Uses of History and the Third Wave of Europeanization. In: Malgorzata Pakier and Bo Stråth. (2010). A European Memory? Contested Histories and Politics of Remembrance. Oxford. 38-55.

Macdonald, S., (2009). Cosmopolitan memory. Holocaust Commemoration and National identity. Memory Lands. Heritage and Identity in Europe Today, Routledge. 188-215.

Mälksoo, M., (2009). The Memory Politics of Becoming European: The East European Subalterns and the Collective Memory of Europe. European Journal of International Relations, 15:4. 653-680.

Rich, D. A. (2015). The “Trawniki” Kommando of the Janowska Labour Camp, ‘Against Our Will’ Conference, Jena.

Snyder, T. (2011). Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin. Vintage Publishing.

Browning, C. (1992, 2001). Ordinary men. Reserve police battalion 101 and the final solution in Poland. Penguin Books.

Goldhagen. D.J. (1996). Hitler’s willing executioners. Ordinary men and the Holocaust. Knopf.

Black. P. (2011). Foot soldiers of the Final Solution. The Trawniki training camp and Operation Reinhard. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 25:1. 1-99.