By Amanda Smith

“Let’s Take Back Control”, “Make America Great Again” and make “Nederland Weer Van Ons” (“Make The Netherlands Ours Again”). In the early part of the twenty-first century, governments around the Western world are shoring up country borders, building walls and protecting the values of the “indigenous” people. It would seem that we’re now witnessing a withdrawal from cultural interconnectivity nurtured by the internet and are becoming more afraid of the rest of the world, retreating into nationalist ways of thinking.

Messages of hate can be shared from one side of the globe to the other on Facebook in an instant but can we share empathy and make our cultures understood just as easily?

Connecting Cultures through Museums

Without living in another culture, it’s difficult to understand one but this is where museums such as the Volkenkunde (Ethnology) Museum in Leiden can try to help bridge the gap. Their aim is to showcase stories about “universal human themes” like prayer, conflict, celebration and mourning to show that “despite cultural differences, we are all essentially the same.”

I saw this ideal throughout the museum when I visited it last year, but the exhibition which really caught my attention was ‘De bedevaart naar Mekka’ (‘The Pilgrimage to Mecca’). It’s a temporary exhibition which is in the narrow side-wing of the Asia room of the ground floor. These narrow spaces are in many parts of the museum, showcasing temporary exhibitions and, in all honesty, they’re very easy to miss if you are distracted by the key exhibitions in the central halls. Luckily, the small spotlights of the Mecca exhibition caught my attention before I made my way into the Africa room.

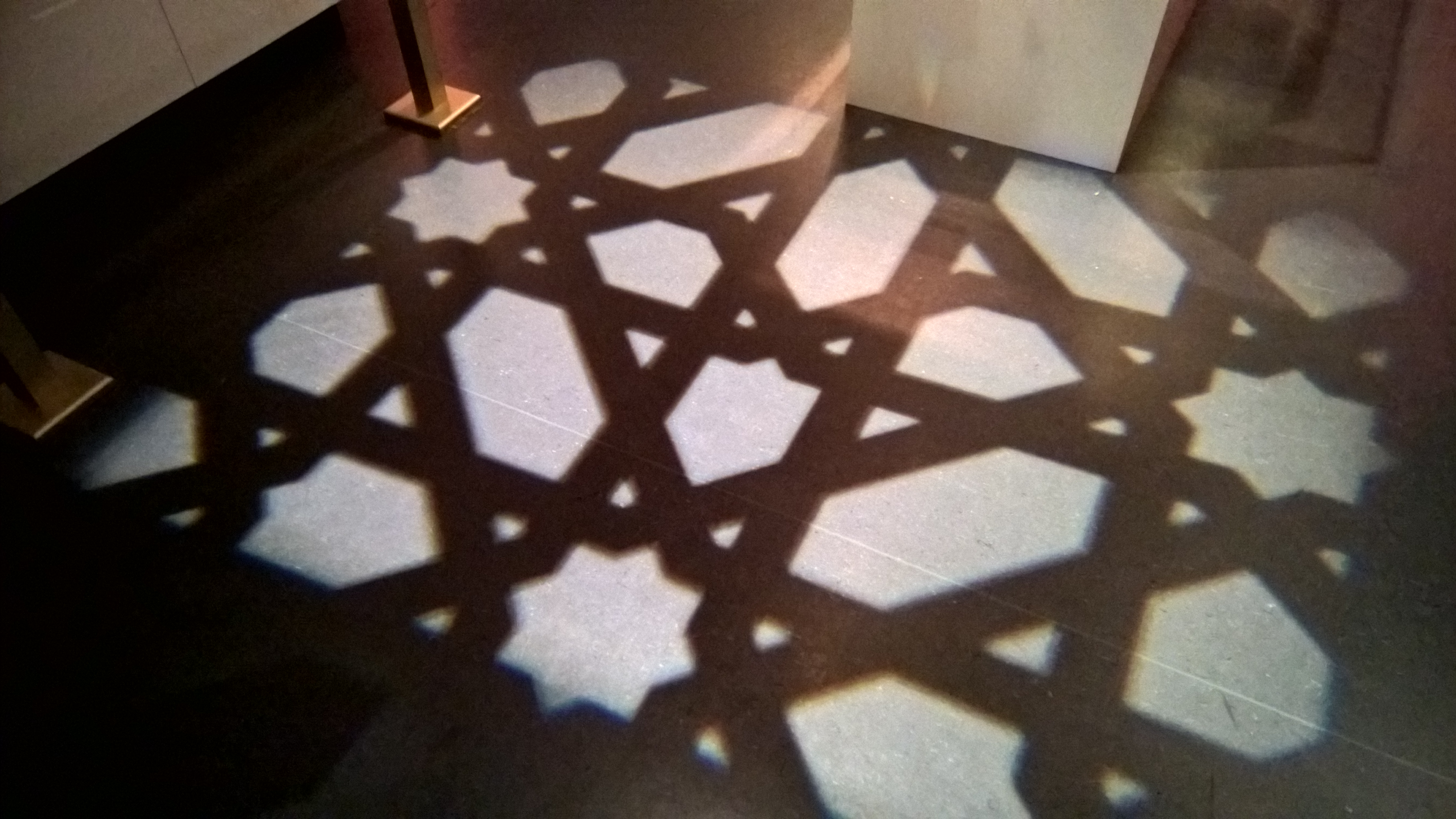

This section has a very different feel to the main collection – the walls were covered with wall tapestries, a nearby wall displayed an old documentary on what the pilgrimage was about, infographic panels gave facts and figures about the Hajj (the pilgrimage to Mecca) and even the lighting aimed at the floor was designed to make you feel as though you are inside a mosque with light streaming through a ceiling window (look up and you’ll realise there’s no window and it’s really just some very clever lighting, check the blog image to see what I mean). The section which draws the most attention is a showcase which displays metal filings swirling around a small square magnet in the centre, intending to represent the draw of Muslims to the Black Stone in Mecca, the destination of their Hajj.

Contact Zones

The exhibition was a peaceful space to be in and it was interesting to learn more about the facts and the figures, and to see some of the treasures, of the Muslim community. But aside from the documentary I don’t recall whether there were any actual stories from people from that community about what the Hajj means to them. The Volkenkunde Museum mentions in their potted history of the museum online (PDF available in Dutch only) that since the second half of the twentieth century they have been able to work more closely with the communities which they produce exhibitions on. However, it was never obvious whether the Mecca exhibition was co-produced with the Muslim community.

Exhibitions concerning communities can be approached in a couple of ways: the museum can put the exhibition on without any external input, or they can engage with those communities to make sure they aren’t misrepresenting them. The space where museums meet with the community to discuss a collaboration is often known as a “contact zone” in museum terminology. This term often has negative associations because it suggests that there’s a balance of power where the museum is often the one who calls the shots and the community being exhibited doesn’t really get to tell their side of the story.

I was interested in learning more about contact zones to see if anyone had come up with a solution to remove the power relation between museum and community. In their journal article called ‘Legacies of Prejudice: racism, co-production and radical trust in the museum’, Bernadette Lynch and Samuel Alberti talk about contact zones and how, despite the museum creating a space for the communities to express themselves, contact zones can still be present (even unintentionally) because it’s ultimately the museum’s space and so they set the limits. Museums are also seen as traditional authorities, which is a long-standing assumption that has gone unchallenged for years. Bernadette and Samuel also say that because of this, collaborators can be put off from contributing because they feel that they will not change anything and their stories will be twisted to fit the way the museum wants to present it. The main focus of their article, was an examination of contact zones present in the Manchester Museum exhibition Revealing Histories: Myths about Race; at the official opening of the exhibition, no one from outside the museum spoke formally, so the collaboration was hidden or not made obvious to the public.

Bernadette and Samuel argue that for a museum to be truly a 50/50 collaboration, there needs to be a “radical trust”, which shares authority between both parties. Essentially, for a true 50/50 collaboration to work, museums need to give up their control over the exhibition and trust the collaborators more, which means it could take more time for an exhibition to be completed. There are still pitfalls to this radical trust – museums earn their funding by making promises that an exhibition will open by a certain date and they promise that it will display certain content. Without this, they don’t get funded. Bernadette and Samuel don’t give any answers to these complications in this article but if answers could be found, we would be a step further in removing contact zones and power politics in museums.

Are Contact Zones in all Museums?

When reading their article, I wondered if this could have happened in the Mecca exhibition at the Volkenkunde Museum. Despite the museum saying it engages more with the communities it creates exhibitions about, I couldn’t tell you whether this project was a collaboration… and perhaps that’s my point made for me. They didn’t make it obvious. Without transparency from the museums, there’s no way of knowing whether these contact zones exist and the Mecca exhibition didn’t feature any human stories to help determine whether the exhibition was a collaborative effort.

Perhaps, even if “De beedevaart naar Mekka” was a collaboration, it could have been a conscious decision not to include the faces of actual people in it; the museum wants to show visitors that despite our cultural differences we’re all the same. By taking faces out of the display cabinets, the visitor can project themselves onto the culture being exhibited and it becomes easier for them to imagine themselves as part of that culture. This technique gets used in mediums you might not expect – for example, in first-person video games (such as Portal), the player sees the world through the eyes of the character – they never see the character’s body and so it’s easier for the player to project themselves onto the character, regardless of gender or ethnicity. It’s easier for them to feel immersed in the world. In a time where people seem to be increasingly fearful of anyone who is visibly different, perhaps this approach could help to build empathy and create a feeling of belonging to an international community… before we cut ourselves off from each other, build our walls and make all our nations “great” again.

‘De bedevaart naar Mecca’ can still be seen at the Volkenkunde Museum in Leiden until 7th January 2018.

Photo credit: photo is author’s own taken during a visit to the Volkenkunde Museum.

Bernadette T. Lynch and Samuel J.M.M. Alberti’s (2010) ‘Legacies of Prejudice’ article can be accessed here free of charge.

Full citation: Lynch, Bernadette T., and Albert, Samuel J.M.M. (2010) ‘Legacies of Prejudice: Racism, Co-production and Radical Trust in the Museum’ in Museum Management and Curatorship, 25 (1), pp.13-35.