In the last couple of months, I have been working as an intern in an art gallery called Kunsthuizen situated in Amsterdam. My role in the gallery doesn’t involve interaction with visitors, but the desk where I work most of the day is situated on the first floor in an open space of a three storey building, which allows me to be a kind of ‘participant observer’. In fact, I can pick up various comments that visitors make about the artworks displayed but also on aspects of the gallery’s architectural layout in terms of space and the interior design. Since observing visitor behaviour is considered a useful tool in the museum field for understanding ‘facts and actions that are preconditions for learning and non-learning situations’ (Bollo and Dal Pozzolo 2005 in Tzortzu 2014: 329) and, complementary to other research techniques to provide a comprehensive picture of the visitors’ experience, it is very interesting for me to use this opportunity to reflect on the behaviour and the interaction of visitors with the museums and art galleries’ space.

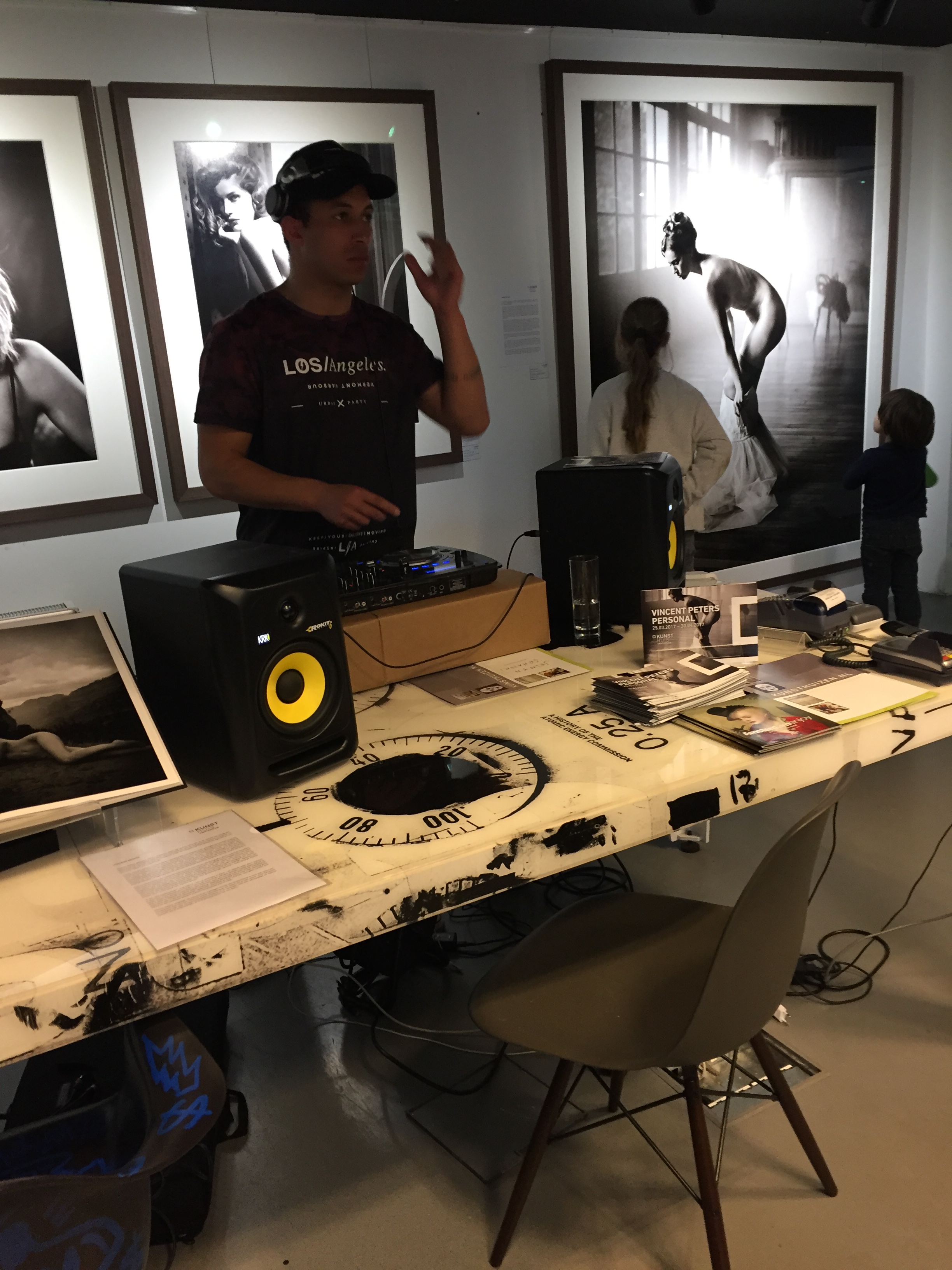

Kunsthuizen Amsterdam started from the passion for the art of the two brothers Henk-Jan and Bart Mulder and over the past ten years has become one of the largest renting art collections of the Netherlands. The Amsterdam gallery has started experimenting with different formats and is trying to create a place that could function as a hybrid between an art gallery and a museum. In fact, a few times a year they organise exhibitions of internationally appreciated and established artists, whose main purpose is not only commercial but to give everyone the opportunity to enjoy contemporary art. Obviously, visitors appreciate the exhibitions, but even more, they enjoy listening and asking questions about the artworks or photography when an artist is present in the gallery for the opening or for book signing. However, on many occasions, I have overheard visitors commenting on the gallery space and interior decoration with almost the same enthusiasm and interest they show towards the artworks displayed. Apparently, the management is also aware of the impact of the exhibition environment and atmosphere on their audience, so that during a recent private view a dj-set was organised as shown in the photo below.

Figure 2: DJ SET (photograph by the author)

Interior design in the service industry

There is a growing recognition of the importance and the effects of interior design on visitors and staff in the service industry and even on patients in healthcare environments. ‘There is increasing scientific evidence that poor design works against the well-being of patients and in certain instances can have negative effects on physiological indicators of wellness.’ (Ulrich 2001:97) For this reason, in the academic health care field, sound research and theories on supportive design of healthcare facilities and how it should help patients, visitors and healthcare staff coping with stress have been carried out(Ulrich 2001). These issues and the importance of physical and environmental factors on visitors’ experience were discussed recently in a lecture at the University of Amsterdam by Annemarie de Wildt, Curator of the Amsterdam Museum and Bernadette Schrandt, Researcher Lectoraat in Cross Media at Hogeschool van Amsterdam who, as part of their jobs, are involved in the design processes and perception of exhibitions. In addition, Tim Zeedijk, Head of Exhibitions at the Rijksmuseum, in a presentation given to heritage and memory master students, conducting a short tour of the museum, emphasised the time and energy that both the architects team and him as curator have put into re-organising the layout of the museum space during the reconstruction works. Tim mentioned that the customer experience can also be influenced by the fatigue of visiting a museum especially if it is as big as the Rijksmuseum and therefore they have tried to design different galleries and exhibitions so that a person can see just one section of the entire museum (staying inside for a shorter period of time) and have the chance to see different objects with the same theme.

The academia of museum studies also dedicates large research to this matter. In the last twenty years with, the rise of the ‘Experience Economy’, it has become clear that ‘what people want today are experiences – memorable events that engage them’(Pine&Gilmore 2007:76) in a sort of personal way’. For this reason, it is even more important than in the past to pay special attention to ‘how exhibits are perceived by visitors through spatial and visual relations’ (Tzortzi 2014:327) and to how museum and exhibition design affects the visitors’ experience. Pine&Gilmore in a very interesting article that speaks about the notion of ‘experience economy’ refer to Michael Benedikt (1987) who underlines how ‘in our media-saturated times’ architecture plays a fundamental role in offering audiences a deeper aesthetic experience of the real. On the other hand, they highlight the fact that there is the risk that these spaces become too artificial and the exhibition design is thought of more for attractive entertaining values than for its functional purposes (Pine&Gilmore 2007).

Exhibition layout and visitor behaviour

Kali Tzortzi an assistant professor at University of Patras whose research interests and PhD thesis focused on the function and use of museum space, exhibition layout, visitor behaviour and experience, thoroughly discussed the interaction between the architectural layout of space and visitors’ experience in his article ‘Movement in museums: mediating between museum intent and visitor experience’. In this article, Tzortzi looks over, first of all, how the concept related to museum design and the laying down of exhibiting spaces have evolved in museums’ history from the Glyptothek in Munich (1815-30), where for the first time ‘the organisation of movement is linked to the organisation of objects’ (Tzortzi 2014: 328) to the reinterpretation of spatial themes in the twentieth century in the Guggenheim Museum of New York. In the Guggenheim, the traditional sequence of galleries is placed instead on a spiral ramp which creates a ‘theatrical element’ to the museum. The glimpse at the historical progression and transformation of exhibitions’ composition helps to highlight the fact that the realisation of a ‘visitable sequence of spaces’ has always been at the heart of the idea of the museum and it persists to be over time until the present day. He then shifted the discussion from a theoretical ground to the empirical by using five museums as case studies to examine the different layouts and museological concepts: the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern and the Sainsbury (Wing of the National Gallery??) in London, the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona and the new Acropolis Museum in Athens. These real case studies of museums help to investigate the movement of visitors within the exhibition space ‘in relation to different exhibition styles’ (MacDonald 2007 in Tzortzi 2014:329). This research gives an insightful contribution to current discussion on models of museum and exhibition design and it helps understand that organising movement in museums is not just about ‘getting people to all galleries, but about affecting the order in which things are seen and how they are seen’ (Tzortzi 2014: 346) which is at the base of the ‘construction of the curatorial message’. It makes clear ‘how patterns of accessibility and visibility’ influence the way visitors read and perceive objects and displays. Moreover, the different types of exhibition layout and movement shape the diverse experiences ‘today’s museums offer their visitors’ (Tzorti 2014:347) which is, as I stated earlier on, something that people look for and that creates a certain kind of museum individuality.

Kunsthuizen management is planning to open a bigger art gallery space which could have similar museum functions. When planning the exhibition design it will be essential to keep in mind and to take into consideration this useful academic insight which can really make a difference to their offerings and to the visitors’ experience. Moreover, I think that all curators including those crafting exhibitions that have not been designated as in law or by professional accreditation, or that have hybrid collections, should pay attention to how they frame the works (of art ) and the message they want to convey. Furthermore, in order to meet their vocation and offer a distinctive and memorable experience, it can be really useful to carry out, on a regular basis during or after an exhibition, an investigation on what feelings it evokes to visitors as well as which meanings they might give to the themes proposed.

- Pine II, J & Gilmore, J. (2007), “Museum & Authenticity”, Museum News, May/June, 76-93.

- Tzortzi, K. (2014), Movement in museums: mediating between museum intent and visitor experience, Museum Management and Curatorship, 29 (4), 327-348.

- Zeedijk, Tim, Head of Exhibitions, presentation given to students whilst conducting a short tour of the museum, Rijksmuseum, Friday 18th November 2016.

- Ulrich, S. (2001), Effect of interior design of wellness: theory and recent Scientific Research, Journal of health care interior design, 97-108.