The Egyptian Museum of Turin attracts a great number of visitors every year, and it is one of the most popular cultural sites in Italy. Yet it doesn’t display anything ‘Italian’ throughout its many galleries and exhibition spaces. The museum is in Turin, and its history is inextricably linked to that of the former Italian Royal family, the Savoy, who were originally the rulers of the alpine region of Piedmont, and who started sponsoring the acquisition of artefacts from Egypt since the 18th century. The Regio Museo delle Antichità Egizie (Royal Museum of Egyptian Antiquities) was then formally instituted in 1824. At the time Italy was no more than ‘a geographical expression’ to say it in the memorable words of Count Metternich. A number of republics, city states and monarchies run through the peninsula, with the Papacy firmly rouling a sizeable area in the centre, between the Asburgic north and the Borbonic south. Fast forward about fifty years, and the Savoys had become the kings of Italy, the Austro-Hungarians and the Bourbons were gone, and the Pope was on the verge of a breakdown, to put it simply, because he had been expropriated of his temporal powers, stripped of his lands, and only left with the Vatican to rule. That is to say that he had to act like a religious leader, rather than a king, for the first time in a long, long time, and he certainly wasn’t happy about it!

What has this to do with the Egyptian Museum of Turin you might ask at this point? Well, let me try to explain where I come from (quite literally!)… The museum was recently criticised by Giorgia Meloni, the leader of a right wing party, because of an initiative that started in January 2018, and will be running for about three months. The initiative consists of a special two for one offer, thanks to which; people from Arabic speaking countries might avail of two tickets for the price of one in order to visit the museum. Meloni expressed her disdain via social media at first, and then by protesting with a group of her followers outside the museum. The director of the Egyptian Museum of Turin, Christian Greco, actually came out of the museum to explain the reasons behind his choice directly to the politician. He calmly pointed out that promotions of this kind are part of his strategy to get more people to visit the museum. He said that there is a similar offer on Saint Valentine’s day, and that people can visit the museum for free on various occasions, and also that students receive a discount.

Greco’s reasoning did not seem to produce any effect on Meloni and her followers that have kept their polemic alive on social media. Their problem is that they see this initiative as racist…towards Italians! They simply don’t seem to be able to get their head around the fact that people that speak Arabic might have an interest in Ancient Egypt, and that the director might want to encourage them to visit the museum by introducing a special offer for a limited time of the year. All they see- together with Meloni, is a bunch of terrorists, immigrants, and criminals that are given privileges over Italian citizens! This is evident by looking at Meloni’s Tweet, and Facebook posts (see for instance the post published on 9/2/2018) on this matter and by the responses to them.

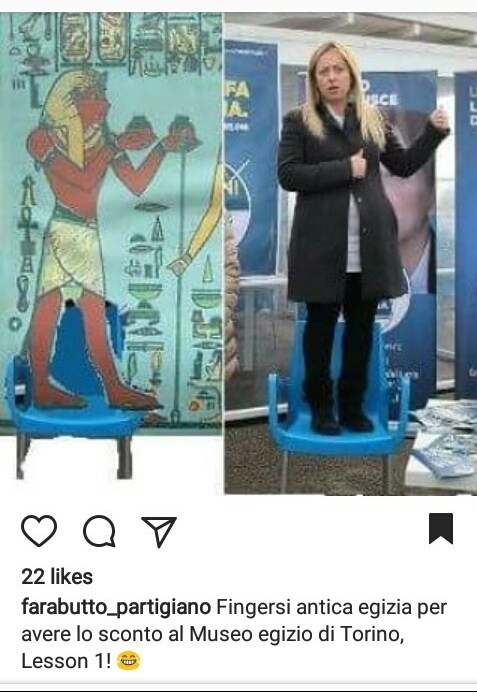

On the other hand it is important to notice that many people were very vocal about defending the director of the museum and his choices, highlighting how the museum is privately financed and how these initiatives have all contributed to make the museum one of the most visited in Italy. This can be seen for instance, in the comments on the Egyptian Museum Facebook page under the post in which the director thanks everyone for their support of his management and of the museum, but also by looking at some of the funny images that have been posted on Instagram such as this:

Dario Franceschini, the current minister of cultural heritage and activities and tourism has also defended the director’s initiative on Twitter. In his post Franceschini referred to the fact that some exponents of the right wing had suggested that Greco would have been removed from his role as director if the right wing came to power after the elections of the 4th of March. His post also created a wide response with people either attacking, or indeed defending the director due to their own political beliefs.

Italian cultural institutions in general have also defended the director through social media. For instance, the College of Egyptology of the University of Pisa has posted a message in solidarity with Greco though their Facebook page.

An online petition has also been created to support Greco’s initiative, and it is available here. The petition points out that this initiative of the museum has been hijacked for political ends by the far right. And this is really the important point about this whole polemic. What really comes across from reading the negative comments towards Greco and his idea, is that he allegedly wants to favour foreigners with his initiative, and specifically Muslims. This racial and religious hatred is pushed forward by the far right, which wants to define what it means to be Italian, and ‘patriotic’ as being against immigrants from Arab countries. This is because in their opinion these people are all Islamic fundamentalists that want to make Italy a Muslim country, with the aid of the left wing.

They pass this dangerous message to their voters by stressing that Italian heritage has no contact points with Islam, and that it does not encompass any fundamentalist approaches to religion. We are not like them, they say, we have never been like them.

Archaeology is also employed in this regard, in order to showcase how archaeological treasures are valued and appreciated by Italians, while in Arab countries they are dismissed, because they belong to a time before the advent of Islam. In the specific case of the Egyptian Museum, the equation is that there is no point in bringing the Arab community closer to Egypt’s ancient past, because they can’t, and they don’t want to care about it.

The fact that archaeology has often been employed for nationalistic purposes is not new, and much has been written academically on this matter. One example is the text by Kohl (1998) , in which he explains how archaeology has been used to write, and to rewrite, the perceived past of countries, since the early days of the discipline. More recently Mirjam Hoijtink (2012) wrote more specifically about the topic of the connection between the collecting of Egyptian antiquities and nationalism in the 19th century, in her book- ‘Exhibiting the Past : Caspar Reuvens and the museums of antiquities in Europe, 1800-1840’*. She also mentioned Drovetti, the man that collected the greatest part of the collection now in possession of the Egyptian Museum of Turin. Drovetti was one of the major collectors of antiquities in the 19th century, and he had worked for the French government all of his life, before selling his well renowned collection to the Savoys, (who were also a French aristocratic family) contributing to make the museum of Turin the most important one in the world, after the one in Cairo.

Nowadays this nationalistic message hidden behind heritage is spread even more easily through social media, which allows politicians to reach the wider public with their posts. The fact that people can then add their comments under the original post creates even more confusion and misinformation about heritage, as well as other topics. And at this point my original observation about the fact that the Egyptian Museum of Turin was instituted at a time when Italy wasn’t even a country, might start to make sense.

The museum itself was not opened for the benefit of Italians, because there were no ‘Italians’ when it was instituted! In addition to this, the inhabitants of the Italian peninsula were never a united people before the end of the 19th century, and it sure wasn’t an easy process to have many different traditions coming together, including the ‘fundamentalist’ Catholic one, or the ones influenced by contact with North Africa in the South, or by Central Europe in the North. So why, I wonder, being Italian ‘patriots’ should mean to exclude people with a different background, rather than encouraging them to enjoy the museums and sites in our country? Let’s hope that in the future social media can become a means to bring people together, rather than a way to spread hatred and prejudice!

*Ref: Hoijtink, M. (2012). Exhibiting the Past : Caspar Reuvens and the museums of antiquities in Europe, 1800-1840, Turnhout : Brepols.

The feature image is in the public domain and can be found here.