By Anna Gay

By Anna Gay

BlackPanther , the film by Marvel Studios, has been taking social media platforms by storm by emphasizing the power of People of Color in pop culture since its release at the end of January. I can hardly go through my Facebook feed without seeing the tremendous impact this film has had on Black Heritage in the United States and with the political tensions over Black Lives Matter and increased racial tensions, this film is supporting the movement for more recognition of Black Heritage. However, this film by Ryan Coogler is not just stirring things up on twitter, instagram, and Facebook, it is sparking important conversations in the realm of museum authority.

In a post by Casey Haughlin for the blog The Hopkins Exhibitionist entitled Why museum professionals need to talk about Black Panther, starts the conversation that museums as institutions need to have about the representation of artifacts from former colonies. It is no secret to museum and heritage professionals that there are questionable ethics behind some collections in some of the mostinfluential museums across the globe. The dialogue of this article begins with dissecting a scene in which the relationship between colonial authority and West African artifacts commences within the film. Without revealing too many spoilers, the resentment felt by the villain Killmonger while gazing upon artifacts of African nations is expressed and is used as his driving force to liberate the still colonized Black world within the film. His sentiment mirrors the real life realities of museums and People of Color, especially those from colonized nations.

How did these museums (both fictional and real) use their authority to squelch Black Heritage for so long? One answer is simple. Authority. It should be no surprise that museums have established themselves as authorities of authenticity and have used that authority to create spaces in which the origin of artifacts does not play a major part in the object’s story. Up until recently, how artifacts were acquired was not important to visitors, since they trusted the institution to be truthful. Killmonger’s rage in this titular scene in Black Panther openly defies that authority (as any Marvel superhero or supervillain would be expected to do) and directly expose the inaccuracies of ethical museum collection.

I believe a major issue with museums and their authority is that these institutions claim to have the jurisdiction on Black Heritage simply because they hold those objects within their walls. What museums actually are displaying are aspects of Black History that the Black community do not have agency over. David Lowenthal addresses the difference between history and heritage in his piece Fabricating Heritage, and states that “ history is for all,heritage is for us alone”. Heritage is something that only applies to those who identify with the myths, stories and traditions that fall within it.

Now imagine that what we have been shown in mammoth museums such as the British Museum is now not part of human history, but each room only applies to a certain group and only those who identify with the represented cultural group are able to take away a meaningful experience. This is an idea that does not sit well with the public as we believe that everything that has been made belongs in the fabric of humankind as part of our history. However, as Lowenthal states “history seeks to convince by truth and succumbs to falsehood”, and exposing that falsehood relies on people, either real or fictional, to confront those entities that claim to have the authority on history. Black Panther and Killmonger are taking the colonial history of West Africa and transferring it into the realm of Black Heritage within the film. Hoping by showing this scene, we are one step closer to reclaiming something that is not history but historical and a part of their heritage in the eyes of the Black community.

This post by Haughlin makes a clear assumption that this scene was chosen intentionally to spark dialogue and perhaps call for change in the museum sector. This scene made the cut to add to the many other contemporary issues that People of Color face in their representation. This audience has been denied agency for a long time, and who would have thought that a movie in the Marvel Comic Universe would bring this issue to the public eye. For everyone who sees this film, they will know that museums will no longer be able to confidently say that they are the authority on the authenticity of their collection unless proper agency has been given to those being represented. Haughlin is correct in saying this scene has started a very important dialogue in the museum community on repatriation of artifacts that were stolen during the colonial period; however I would like to add to this conversation by emphasizing that heritage of former colonial communities not be displayed as neutral history. While the likes of Killmonger are more likely to stay within the comic universe, Black Panther is making an impact that is long overdue in reality.

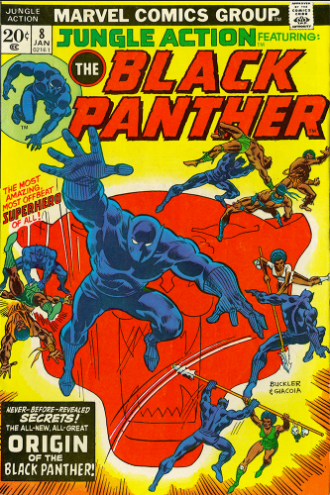

Featured Image: www.flickr.com/photos/vculibraries/40121109372/

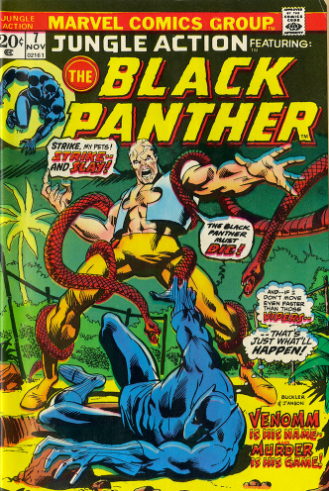

Image: www.flickr.com/photos/vculibraries/25281641367/