The looting of antiquities has long been one of the main problems associated with the preservation of heritage. Objects that are considered to be aesthetically pleasing, or that are made of precious materials are usually the most sought after in the antiquity market. This market usually thrives wherever there is a war, or in areas affected by poverty. What can be done to invert the looting trend?

Sarah Parcak is a space archaeologist, a university lecturer at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a TED Fellow. She won the TED Prize in 2016 and speaking at a TED Conference in the same year explained that she had used the money attached to the prize to fight looting in the most singular way in a talk titled Help discover ancient ruins — before it’s too late.

During her speech Parcak explained how the question of looting is presently very relevant in different areas of the world, but that the problem is not only the fact that many people, usually driven by the perspective of earning money to help their families, approach looting as a form of subsistence. Parcak also points out that the main responsibility for the growth of this illegal market lies with the middle men who profit from it, and ultimately with the people, and the heritage associations that turn a blind eye to the provenience of the antiquities that they purchase.

This has been considered from an academic point of view as the main issue when considering the impact of the looting of the world’s heritage. For instance- and this is just one of many example of academics writing on this topic, Staffan Lunden* points out how, although antiquities are looted in every country, richer and politically stable countries employ more people to control this traffic, and they also have the capacity to punish looters and dealers. While in countries that are going through a war, or economic hardship, these controls are harder to carry out, and this leads to a wider illegal antiquities market. Lunden also highlights the role that heritage professionals, and the concept of heritage in western countries, have in promoting this illegal trafficking.

This is because of the fact that in the heritage field objects are usually seen as important according to their aesthetic value, and therefore they are displayed in museums in a way that enhances their beauty, rather than the context in which they were found, and their original purpose. In addition to this, looted objects are often seen by their buyers as having been ‘saved’ from the lack of care that they would be subjected to in the country from where they were retrieved. This is why- according to Lunden, that people who donate their private collections of objects of dubious provenience are usually ‘awarded’ by museums and similar organisations, which often even dedicate the room in which the objects are displayed to the relevant donors.

How can the trend be inverted?

The main question in regard to the illegal trade of antiquities is then, how can this trend be inverted? Is there something that really can be done when so many people seem to benefit from this business?

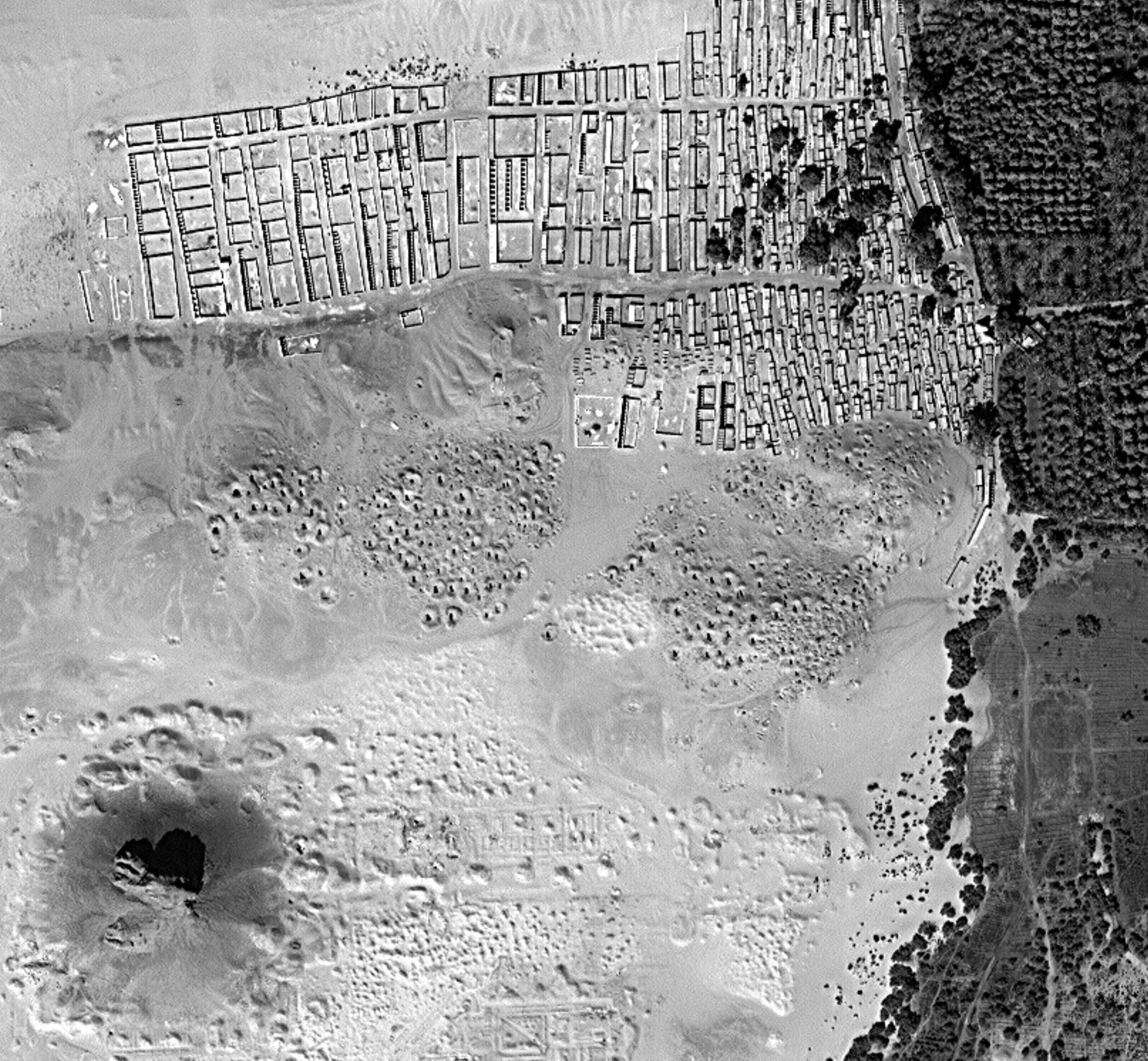

Well, Parcak might have a solution! As she explained in her presentation at a TED Conference in 2016, she is a space archaeologist, and this means that she tries to find undiscovered archaeological sites by scanning pictures that have been taken from space. By looking at these images she can see features underground that are hard to see from earth, discovering sites that have not been found before. Doing this she can also see the pitt marks left behind by antiquities looters, and map them.

Parcak explains for instance, how she has noticed an incredible spike in antiquities looting in Egypt in the last few years, and how she has been able to go to the places that had been recently looted to survey them. There she discovered other features that were of no interest for the looters but, that can still provide important information for the archaeological records of those areas.

Crucially, Parcak’s perspective on heritage is that what is important is not the object itself, but what as humans we can learn from an ancient site. She considers the ‘little things’ as the real treasure to be found, and as what can make everyone aware of our common history as humans, rather than our national or cultural differences.

As she brilliantly puts it in her speech: ‘…On the dig, surrounded by emerald green rice paddies, I discovered an intact pot. Flipping it over, I discovered a human thumbprint left by whoever made the vessel. For a moment, time stood still. I didn’t know where I was. It was because at that moment I realized, when we dig, we’re digging for people, not things.’ Or: ‘It is not the pyramids that stand the test of time; it is human ingenuity. That is our shared human brilliance. History may be cyclical, but we are singular.’

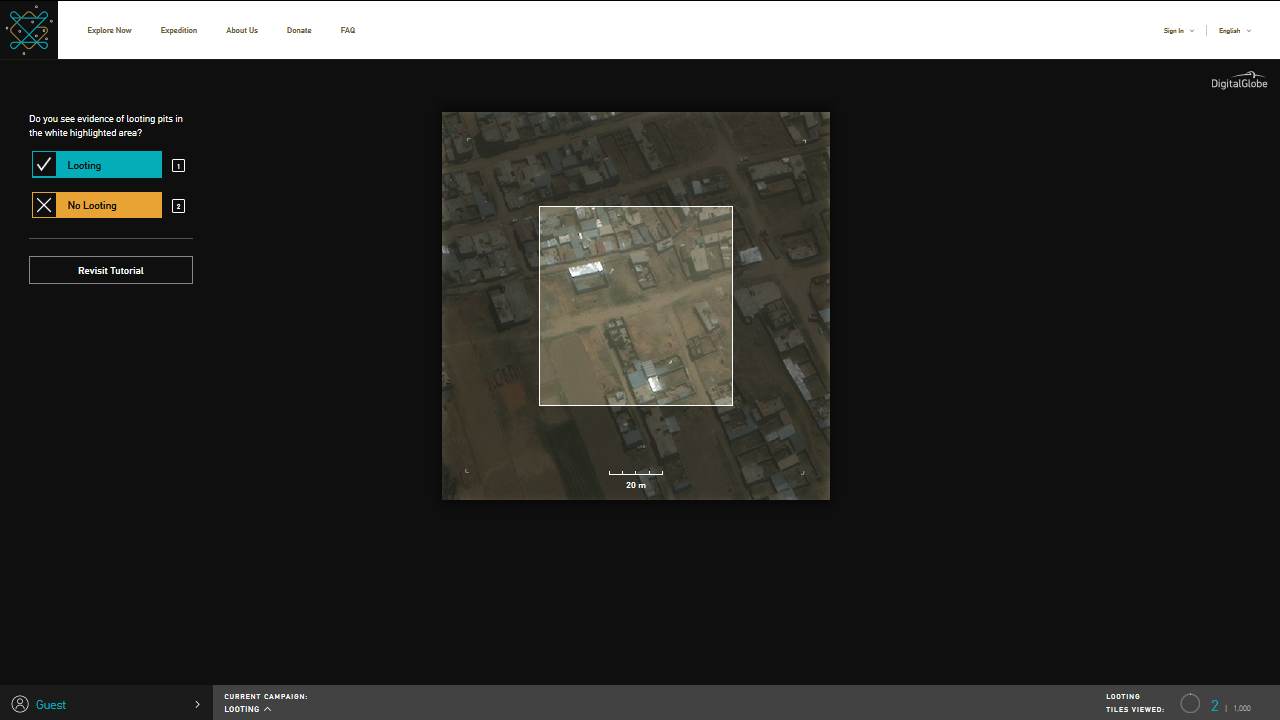

This is why Parcak has used the money that come along with the TED Prize that she has won to create a web programme named Global Explorer, where everyone that is interested can contribute to find undiscovered underground features and loote pitts. The process is very simple, all that users need to do is to go through a quick tutorial, and then start looking at images of a certain area from space, indicating if they can see any features. The users are not provided with any coordinates on the area that they are viewing, in order to avoid giving information about the location to potential looters. All the data is then collected and used to learn more about the features with the help of local governments.

In this way, new sites and looted sites can be successfully marked, and more can be learned about their status. At the same time, the process of discovery is democratised, and everyone can give their contribution to help to stop antiquities being looted. This combination of new technologies, and a new approach to heritage could be what it is needed at an international level to truly invert the trend of looting and the illegal dealing of antiquities, as well as helping everyone to be more invested in protecting and learning about our heritage.

I have to admit I have started using Global Explorer as soon as I found out about it, and it really is easy to use and quite fun too! I would recommend everyone to give it a try… you might make the next great discovery of our time… before it is destroyed by a looter!

(Screen shoot of Global Explorer where you can see how it works)

(Screen shoot of Global Explorer where you can see how it works)

Cover Image: South Dashur, as seen by satellite in 2014. While this site was virtually unlooted before 2011, the site is now pockmarked with looting pits. Photo: Digital Globe

* S.Lunden, Perspective on looting, the illicit antiquity trade, art and heritage, Art and Law, 25(2), 2012