Commemoration of Jewish Heritage in Lviv: The Golden Rose Synagogue and the Space of Synagogues

By Nazlu Laird & Martina Montemaggi

‘The entire history of the Jews in this city comes together in this close, fenced in little courtyard…And from the old walls of the synagogue the cold, the frost of the ages beat down, the shudder of four long centuries…’ Majer Balaban

On our excursion to Eastern Europe we decided to research and present on the ruins of the Golden Rose Synagogue in the former Jewish Quarter in Lviv as we felt the site perfectly encapsulated the theme of the excursion; conflicted pasts, contested heritage and competing memories. Whilst preparing for our trip we decided that we wanted to address how the tensions between the needs of tourism, memorialisation and the needs of the Jewish community were met, came into conflict, or affected the site. With this idea as our primary focus we set off on our journey, and what we encountered in Lviv vastly extended our knowledge and understanding of the kinds of issues and discussions that stem from such a site such, particularly in the context of Western Ukraine. The site of the Golden Rose Synagogue of course bears myriad significance for us as students of Heritage and Memory Studies. After spending time in Lviv and after interviews with several key figures of the memorial project we began to realise that the significance of the Golden Rose and the memorial itself should be addressed from several angles. It is for this reason that our following entry will discuss, firstly, the bottom up approach to heritage through the Space of Synagogues project, secondly the role of architecture in Holocaust memorialisation and thirdly the role of tourism in relation to Jewish heritage in Lviv.

Before we go into more detail of our actual research we believe that it is useful to provide a brief historical overview of the site. From its construction in the late 16th century, the Golden Rose thrived as an important centre for Jewish faith, not only in Lviv but also throughout the entire region of Galicia. The Golden Rose synagogue was actually built due to the fact that there was not enough space in the Great City Synagogue for the Jewish population of Lviv. These synagogues also neighboured the Beth Hamidrash school. However, the Golden Rose Synagogue has a turbulent history from the early 1940s onwards; looted and then devastated by the Nazis with the support of Ukrainian paramilitary organisations in 1941-3, it also lay in ruins throughout the entire Soviet period. In the 1980s municipal authorities carried out some conservation work and in the 1990s a computer simulation was made by architectural historian Sergey Kravtsov showing the synagogue at all stages of its history. In 1998 the site became incorporated into the designated UNESCO World Heritage site, the old town centre. In 2011 plans were made to turn the site into a hotel for the UEFA cup but after international pressure these plans were abandoned. Since then, the program for the regeneration of the Jewish quarter in Lviv has brought the issue of what to do with the site forward. This highlights the well-discussed issue of Jewish heritage preservation where there is an absence of a Jewish community; after the Second World War, Lviv had lost lost 99.6% of its Jewish population.

Podcast:

A Bottom up Approach to Heritage: The Space of Synagogues

Holocaust memorialisation in Ukraine is a relatively new phenomena. As Mikhail Tyaglyy, of the Ukrainian Centre for Holocaust Studies, states, ‘Over 25 years of independence, our state has never come up with a proper policy on the Holocaust, either because they were simply not interested or because it did not fit in with their particular ideological bent.’ [1] Due to Ukraine’s complicated struggle for national independence and difficult narration of crimes committed against Jews during the Second World War it is unsurprising that Holocaust memorialisation carries with it complex discussions in Ukraine. As Daniel Hoffman, freelance journalist writing for Haaretz states, the ‘issue of commemorating sites and individuals connected to the Holocaust is divisive in Ukraine, where anti-Russian sentiment is rife and streets were named recently for pro-Nazi collaborators whose troops killed Jews.’ [2] However, the Space of Synagogues appears to be a trailblazing approach to commemoration in Ukraine, perhaps showing a development of new approaches to memorial pedagogy. Dan Peleschuk, freelance journalist of Eastern Europe, writing for Public Radio International states, ‘It’s no ordinary memorial. Local officials, experts and international planners all came together for what observers say is a Holocaust commemoration project that’s an achievement in both historical memory and urban planning. They say it’s an example for the rest of Ukraine, where monuments are often commissioned by bureaucrats or well-connected businessmen, with little input from experts or consideration for the local community.’ [3]

At the time that we chose to research the Golden Rose Synagogue the Space of Synagogues Project was well under way. The project began as an open design competition as part of the 2015 festival Jewish Days at the City Hall: Common Heritage and Responsibility. The project can be termed as a bottom up participatory approach to heritage. It involved a large number of actors both local to international, they are as follows: Executive Committee of the Lviv City Council, the city’s Office of Historical Environment Preservation, the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, the German GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit), Lviv’s Hesed Arieh Jewish charity fund, the US-based Gesher Galicia genealogy association and the Israel-based Association of Commemoration of Lwów Jewish Heritage and Sites.

The competition saw 36 projects presented and the winning entry gained the chance to design a memorial at the space where the Golden Rose Synagogue, the Great City Synagogue and the Beth Hamidrash School once stood. The participatory approach meant collaboration from both professionals and local residents with the purpose of understanding the site from a number of points of view. Local residents were involved in the project through a workshop in which they were asked questions such as; what they thought and knew about the site, its history and the neighbourhood? What they would suggest architects improve at the site? What the architect should know? And, their ideas on how to keep the square? The results of the discussion were put on the Internet so that everyone could have the chance to access them. This showed a real effort to involve a wide range of perspectives, from people with knowledge of the site to those who lived in the area and to experts and local and international Jews. The project has been praised for its bottom up approach and arguably contributed to its ultimate success.

Memorialisation and Architecture at the Golden Rose Synagogue

‘It’s a beautiful city, but also a graveyard for 150,000 Jews.’ Eli Brauner (Brauner’s ancestors built the Golden Rose Synagogue)

The memorial that can be seen at the site of the Golden Rose Synagogue today is the result of the competition. German landscape architect, Franz Reschke, whom we interviewed for our research, designed the winning entry for the competition.

The absence of a complete synagogue building is the central aspect of the memorial, as Ada Dianova, Director of Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation Hesed Arieh, described in our interview with her at Hesed Arieh (discussed further in this post), ‘the space feels like an open wound’ within the tightly compacted old town. As you approach the memorial the unlikely open space is telling. The ruins of the inner space of the synagogue, ‘which normally would only reveal itself to worshippers who came in to pray – is wide open for all to see.’ [4]

In our interview with Reschke we asked him what his concept behind the design was, he explained that he tried to let the site speak for itself by not bringing too many vertical structures, too much information or too many objects. In Jascon Francisco’s (who will be discussed further in this post) essay ‘the Jewish as Ruin’ he discusses how to read a ruin, he suggests ‘perhaps we should not try to read a ruin for what it once was or a fragment of something else, something lost or something that existed earlier in time’ rather we should read a ruin ‘as a whole unto itself.’ This idea is reminiscent of how Reschke described his work, as letting the site speak for itself and placing importance on the physical ruins. As we saw when we visited the site, the minimalist concept has played out. Reschke described his work as ‘tracing’ and working with existing things; he explained that working with the traces of the former buildings was important as well as outlines of what had been there before. For example, what we could see on our visit was faint traces of Hebrew letters and frescos emerging through the North wall amongst the decay. As well as the foundations of Beth Hamidrash, which were cleared of concrete and marked simply ‘Venezian Terazzo.’ The only other text that can be seen is an inscription telling a very brief history of the site. This concept of minimalism when it comes to Holocaust memorialisation has been well discussed by scholars. The impossibility and problematic nature of making an artistic statement when it comes to visually representing the historical experience of the past is an important discussion when it comes to a site such as the Golden Rose. Scholars have discussed the Holocaust as unrepresentable and the inability to create art that portrays the unspeakable suffering of the Holocaust. Often what can be seen in Holocaust memorialisation is that a simple object can be a metaphor for both silence out of respect for the memory of the tragedy or the inability to speak of the tragedy without imposing a new meaning on the story.

In our opinion, Reschke’s design is respectful of the site.He explained further that he thought a lot about the surface of the stone that could still be seen, he explained that on the one hand he wanted not to design too much, but also that the result should not be insensitive or too rough. Cutting the surface and opening the structure of the concrete results in a subtle texture and lightly warm colour of the heavy elements. Reschke informed us that his design for the memorial is temporary, that it can be changed, altered or reversed if anyone were to wish it so. Temporality is an important aspect of memorialisation, Young discuss the fact that once a memorial is installed that it ‘petrifies history, signifies a shaky regime in need of a symbol, and is incapable of modernity.’ [5] Young also discusses the fact that we should place less emphasis on memorials themselves and place more emphasis on the needs of the community for memory. In our opinion, Reschke’s design incorporates these important aspects that Young is discussing, by making the memorial something that can be reversed, the artist has shown that he is aware of the needs of the community and the temporal nature of memory. Whilst Young mainly theorises on German, Polish and American cases of Holocaust memorialisation his ideas are still useful in examining this Ukrainian case, however, we must bare in mind that the position of Germany and Ukraine are vastly different in this context. In this case we must remember we are dealing with memory through a different lens, in the context of post-communism and the re-writing of history after independence.

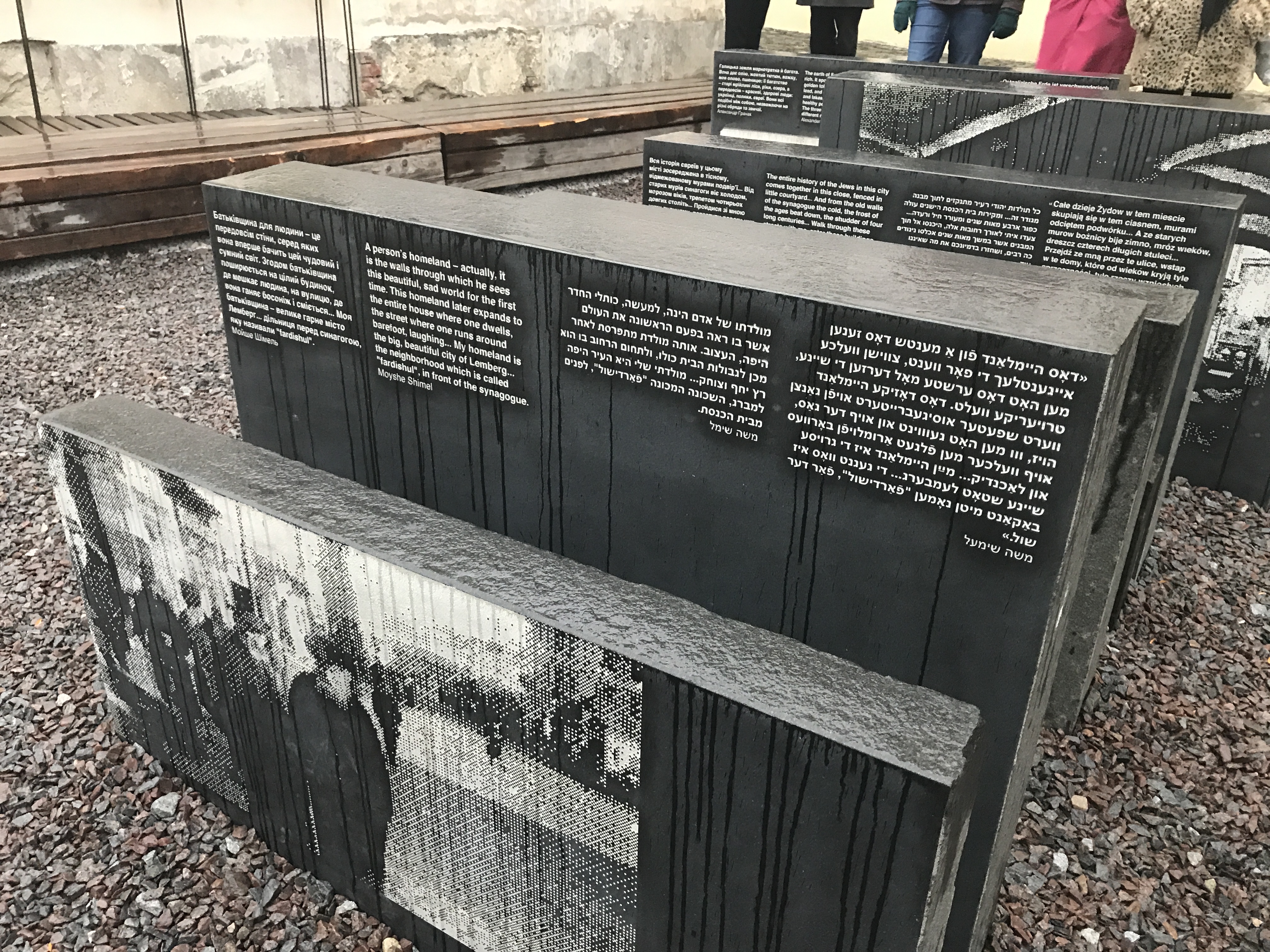

On the site of the Golden Rose there is also an installation called ‘Perpetuation’ designed by artist, Sophie Jahnke, who worked in collaboration with Reschke. The installation consists of 39 dark grey stone tablets, reminiscent of headstones. These stones are engraved with grainy images and inscriptions of prewar Jewish life in Lviv, quotations from former residents about their lives in Lviv, the Holocaust and their lives after the Holocaust. These inscriptions were an important aspect of the previously discussed participatory approach. The selection process for the quotations on the stones involved many local residents and scholars who submitted suggestions and were voted upon by those involved with the project, this particular process was lead by Ada Dianova. These quotes take the visitor to the site on a physical journey as you walk from one end to the other, you are walking through history as told by its witnesses. For example, a quote from Melanie Vogel, an artist and part of the Polish Avant Garde Movement, who died in the Lviv ghetto, can be read. At the time of our visit merely steps away was a temporary exhibition at the Museum of Ideas, which focuses on tracing the steps of Deborah Vogel. This small connection added another dimension to the memorial.

Public treatment of the memorial/use of the memorial counter to its original context

We decided to look at the memorial from this angle due to the well-known ideas of James Young, who suggests that when it comes to Holocaust memorialisation we should also look at the treatment of memorials and not only discuss how they should look. As well as this, the photography of Jason Francisco, artist and essayist, who has spent time photographing synagogues in Poland and Ukraine furthered our interest in this angle. We got in touch with Francisco and discussed both his work at the Golden Rose and the use of the memorial in general.

Whilst conducting our site analysis we sat by the Golden Rose Synagogue over different periods of the day watching how people acted at the site, this produced some interesting results, we saw many people stop and take note of what was there, we saw people read the inscriptions and we also witnessed people taking selfies at the memorial. However, the biggest crowd of people on that cold winter day were in fact visitors to the adjacent restaurant. However, as Francisco spent a lot more time at the memorial than we could have – his current project focuses on how the memorial is being used at all times of day – we asked him what he saw there in relation to how the memorial is being treated. His response is as follows, it functions as a ‘Public meeting space that attracts visitors for reasons having nothing to do with its history, or with the practice of memory. Many visitors like the space because it is clean, attractive, well-lit, hip, and located in a part of the city that increasingly has the character of an adult playground, especially at night and on weekends. I have seen (and photographed) all manner of activities there that are, at least on the surface, altogether apart from the acts of contemplation that the memorial was designed to invite, especially drinking and carousing, and sometimes things that are patently inappropriate (most notoriously, kids jumping the low fence to use the Golden Rose as a place to piss on the ruins of the synagogue itself). How a site does or does not change the culture around it is the open question. Exactly how a city learns to receive what a memorial stands to give is also an open question, and there is no blueprint for this.’

As well as this, both Reschke and Francisco discuss the idea of surveillance in of the presence of a guide at the site as a response to vandalism or what is deemed as inappropriate behaviour. However, this leads us to larger questions of memorialisation and who decides how a site should be interpreted and how closely it can be monitored. Our guide in the Jewish Quarter, Vladyslava Moskalets also discussed the issue of vandalism at the site, however, she described the fact that this was not unique to the Golden Rose memorial, as other sites of Jewish heritage within the city are also being regularly vandalised.

It is clear from our own site analysis and the photography of Francisco that the site is generating attention from locals and tourists, however, it must also be understood that commemoration of Jewish Heritage in Lviv has some way to go.

Controversies Surrounding the Space of Synagogues

In 1939, Lviv was home to 110,000 Jews, a third of its total population. After the Second World War many of the remaining Jews of Lviv fled the country meaning that much of the Jewish community that resides there now, emigrated to Lviv much later and do not have local roots. As James Young asks, ‘How does a city ‘house’ the memory of a people no longer at ‘home’ there?’ [6]

With the intention of offering the full picture, it is worthwhile to note that one small part of the Orthodox Jewish community represented by Meylakh Sheykhet, Director of the Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union of Lviv, expressed strong opposition to the Space of Synagogues project. Sheykhet’s criticism of the project was reported by local and international press. He attempted to bring the project to a halt in many ways, for example berating construction workers on the site (read more). He has also sent caustic letters and mails to foreign journalists, to the architect and even to Ms. Merkel. He filed several lawsuits based on the approach of the Rule of Laws as he argues that cultural heritage values should not be negotiated for commercial reasons. In 2014, he managed to win a case and a ‘Ukrainian court issued an injunction against the city’s plan to move ahead with designs for memorial projects in three Jewish sites in Lviv, including the Golden Rose Synagogue complex. The Higher Economic Court of Ukraine ruled that the plans did not conform to local and international standards and procedures.’ However, the city obtained a permission from the Ministry of Culture to proceed at the Golden Rose with the design. However, Sheykhet sued again, arguing the project violated the 2014 court ruling. A verdict was expected at the end of 2016 but the verdict has not been given yet. Sheykhet argues that the main aim behind that project has been to create a public park at the expense of a Jewish heritage site in a central area of the city and to serve the tourist industry interests. He thinks on the other hand that a synagogue should be rebuilt in that space and he has lobbied for funds.

Ada Dianova, involved in the Space of Synagogues project, who we interviewed during our stay in Lviv, somewhat disagrees with this position. She stated, ‘the spirit, the dead atmosphere that still exists in the ruins and in the remaining walls of the original Golden Synagogue would not be existing anymore there. So it would be a new building with a new atmosphere.’ She added that a new synagogue in the city with a current Jewish population of 1,200 people is unrealistic and it is often difficult maintaining the active Synagogue.

Also Sofia Dyak, director of the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe in Lviv, the driving force behind the project is in agreement, defends it highlighting the fact that precisely because its central location it exposes countless Ukrainians, especially youngest who knew little or nothing about this past, about the destruction of Lviv’s Jewish community. They both also agree that the development of this memorial is only in its first stage and although it may not be perfect as memorial for active remembrance, it is perhaps more dignifying that leaving the remainings completely abandoned or leaving it as a place where people who use drugs gather. In the next step of the project the terrace of the restaurant (the restaurant is also owned by the same company as the adjacent controversial Golden Rose restaurant) which stands on the foundation of the Great City Synagogue will be removed and the space where the entire synagogue complex stood will be better demarcated.

(re)Presenting Jewish Heritage in Lviv

Whilst Sheykhet’s position towards the project is too radical due to the fact that he thinks it is less disrespectful to leave the space in ruins than this memorial, commentaries along these lines are not entirely unusual as a response to the memorialisation of Jewish heritage in Europe. Ruth Ellen Gruber discusses the fact that within Jewish communities there can be a certain uneasiness with ‘the new role forced on them and their culture and history. They feel used and exploited.’ [7] In fact some ‘governments, including several communist regimes in the 1980s, have not hesitated to play the Jewish card to win sympathy or support from Western nations…honouring lost Jews and their annihilated world can become a means of demonstrating democratic principles and multicultural ideals, regardless of how other contemporary minorities are treated…’ [8]

However, the large majority of Jewish communities in Lviv recognise the positive results of this memorial, they can be to a certain extent unsatisfied about the way the Jewish heritage is represented in Lviv in terms of visibility and quality of presentation. For example, it has been over twenty years since the beginning of discussions and calls for the re-opening of a museum regarding the Jewish past and heritage in Lviv and in Ukraine. Before the Second World War the Great Jewish Museum existed in Lviv. Due to the destruction carried out by the Nazis the collection was deposited in four museums in Lviv for safekeeping. The collection is still held by four museums in Lviv, Museum of Religion, the Museum of History, the Ethnographic Museum, and the Lviv Picture Gallery, however, they do not display most of these artifacts and when they have it has never been in an exhibition exclusively about Jewish culture. Dianovo stated in our interview that assembling together these objects again could create one of the best Jewish Museum in Europe. However, at the time being there is a small museum in the Hesed Arieh building that is not usually only open to members of the centre. We were lucky enough to be able to see this museum during our visit. Whilst this museum is touching and very personal, containing artifacts donated by locals, we felt somewhat melancholy at the fact that this is the only museum that represents Jewish culture in Lviv at the current time.

Furthermore, the choice of hiding such an important and precious collection in deposits says much about how Ukraine deals with its Jewish past and in particular with its difficult heritage, that in this case involves artefacts ‘that are historically important but heavily burdened by their past.’ [9] It is also striking that is has not been acknowledged that the city’s history and jewish history are inseparable. Due to the war in the region of Donbass since 2014 the country currently faces a very difficult financial situation, therefore it is even more difficult to gather funding for such a complex project of a controversial past. As well as this, the decommunisation laws of 2015, which insist the members of the Ukrainian nationalist movement should be recognised as ‘independence fighters’, has led some to worry that Holocaust memory could again be pushed to one side in the context of this contradictory commemoration of history.

However, it is striking that in a city where there are over thirty museums of any kind there is little determination to gather resources for such an important part of Lviv’s history and heritage. However, the unwillingness of of investing in this specific heritage and the difficulties the Jewish community to have its past recognised and represented reminds us that the heritage production is a ‘political process that implies choices among possibilities.’ [10] The crucial question here is who has the responsibility and power to make this selection. ‘The dominant political, social, religious, or ethnic group usually determines which aspects of heritage should be highlighted. [11]

Nevertheless, as specified earlier in this post, after years of silence, repressed or forgotten memories, the situation has started to change and the Space of Synagogues project with the involvement of governmental institutions shows that Ukraine is beginning to officially recognise its Jewish past.

Tourism and Jewish Heritage in Lviv

‘I like to compare Lviv to Krakow,” says Gruber. “Twenty-five years ago, the Jewish quarter in Krakow was a derelict slum. Little by little, because of tourism, things started to happen: Cafés popped out, synagogues were restored, museums opened. Lviv has the same potential. There is enough tangible material to deal with.” [12]

Since the early 2000s, Lviv has become one of the main tourist destinations in Ukraine. The tourism industry has seen an exceptional growth thanks to the abolition of the visa regime for Western tourists since 2005 and the development of train and flight connection with Central and Western Europe. Furthermore, since the new air connection between Lviv and Tel Aviv was opened in May 2015, the number of Israeli tourists coming to the area looking for their roots also significantly increased.

We were in Lviv at the beginning of October which is a low peak season for tourism. It was noticeable however that the street where the Golden Rose is located, which is right in the heart of Lviv’s designated UNESCO area, is bustling with bars, restaurants and shops. Attached to the ruins of the Golden Rose Synagogue in 2009 was a restaurant called the Golden Rose Restaurant. The Golden Rose is owned by non-Jewish company that also owns a popular bunker-themed bar dedicated to Stepan Bandera and his forces. It ‘attempts’ to recreate’the pre-war Jewish atmosphere of the district, yet it does not offer kosher food and has often been accused of commercialising and stereotyping Jewish heritage, by giving customers the option to bargain for the price of their meal and offering customers black hats with curly artificial sidelock.

They also sell Jewish-themed ‘souvenirs’ such as fridge magnets with stereotyped images of Jewish people or Rabbis. Allowing this kind of objects to be sold is a reminder of a general and political attitude that tends ‘to downplay the day-to-day anti-Semitism of the present.’ [13]

Before the memorial was built there were tables and chairs right on the foundation of the Golden Synagogue which for this reason had to be removed. The positive act of removing this was negatively counterbalanced by the fact the same owner expanded its business with a new restaurant just across the road. As part of this new restaurant a large terrace with table and chairs was set up on the space of the Great Synagogue. Even though it is known that in the next step of the project also this terrace should be removed, perhaps the permit to use such a space should not have been given on the first place. It is obvious that the ‘new square’ with the new memorial and lighting is very attractive for tourists and consequently for commercial activities.

Therefore, it is evident that if on one hand the rehabilitation of Jewish heritage sites in cities like Krakow, Prague and Lviv ‘turned Jewish neighbourhood into vibrant urban spaces and boots the physical development of one dilapidated and depressed areas’, on the other hand there are also the negative aspects and doubts regarding the ‘controversial commercial exploitation of heritage.’ [14] Within the process of physical recovery of the Jewish built environment the discussion is still very much open particularly regarding ‘how local Jews and Jewish communities are affected by, participate in, influence, and interact with non-Jewish interest.’ [15] Some important issues remain opened: ‘Where is the line between sincere desire to reintegrate the past and complacent self-congratulation for doing so? Will the new public face and popularity of Things Jewish help to counter anti-Semitism or just contribute to entrenched stereotyping? Is there a saturation point for this type of integration?’ [16]

Final thoughts

To conclude, we have seen two sides of the coin in our discussion of the site of the Golden Rose Synagogue, what surrounds it and the general climate of commemoration of Jewish heritage in Lviv. We have tried to show the specific context and the difficulties that stem from creating a site in this way. Whilst some of our research has shown there is still a long way to go when it comes to satisfactory commemoration for the Jewish community, we have also seen what could be termed as a ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ by using the example of the Space of Synagogues project as a successful model for commemoration. However, with the danger of over simplification of the issue, it has to be acknowledged that there is still a strong social amnesia in Lviv when it comes to commemoration of the Jewish past.

All images by authors unless otherwise stated.

[1] Quote from Mikhail Tyaglyy in ‘Researchers open ‘neglected chapter’ of Ukraine’s Holocaust history, The Guardian, August 2015.

[2] Daniel Hoffman, JTA, Ukraine City Established Memorial at Site of Former Synagogue Wrecked by Nazis, <https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/europe/1.740621>

[3] Dan Peleschuk, ‘why Ukraine’s newest holocaust memorial is so important’ PRI, September 2016, <https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-09-07/why-ukraine-s-newest-holocaust-memorial-so-important> accessed 20/10/17.

[4] Quote from Izabella Tabarovsky of the Kennan Institute on the Space of Synagogues.

[5] James Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, (Yale University Press, 1993). 4.

[6] James Young, At Memory’s Edge, (Yale University Press, 2000). 152.

[7] R.E. Gruber, Virtually Jewish: Reinventing Jewish culture in Europe, (Berkeley, University of California Press), 2002. 18.

[8] Ibid. 10.

[9] Burström et al. (2011) in Nick Carter and Simon Martin, ‘The management and memory of fascist monumental art in postwar and contemporary Italy: the case of Luigi Montanarini’s Apotheosis of Fascism’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies 22:3. 338-364.

[10] Andrea Corsale and Olha Vuytsyk, ‘Jewish heritage tourism between memories and strategies. Different approaches from Lviv, Ukraine,’ Current Issues in Tourism, (2015). 1.

[11] Ibid. 1.

[12] Quote from R.E. Gruber in Daniel Hoffman and Dusty Christensen, ‘Why an Orthodox Jew is Fighting the Construction of a Holocaust Memorial in Ukraine, Haaretz, <https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/.premium-1.720919>

[13] Beckrmann (1994) in R.E. Gruber, Virtually Jewish. 19.

[14] S. Krakover, ‘Coordinated marketing and dissemination of knowledge: Jewish heritage tourism in Serra da Estrela, Portugal’, Journal of Tourism and Development (Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento) 17–18:1 (2012). 11-16 in Corsale and Vuytsyk, ‘Jewish heritage tourism’.

[15] Gruber, Virtually Jewish. 23.

[16] Ibid.