By Nazlu Laird

Deborah Withers’ lecture Contemporary Intangible Heritage and Archiving Memory: Music making in the UK Women’s Liberation Movement, as part of the Innovative Heritage Conference 2014 initially grabbed my attention for a non-academic reason; the fact that I am a devoted Kate Bush fan. Deborah Withers is the author of Adventures in Kate Bush and Theory, a self-published book (HammerOn Press – a grassroots publishing label) about how Kate Bush’s music liberated female creativity and acted as a catalyst for solo female artists’ to express themselves in an entirely new way. Kate Bush aside, her lecture also sparked an academic interest within me due to the fact that I specialised in the broad topic, ‘Women and Feminist Movements in Europe’ as part of my undergraduate degree in History.

Withers’ name also rung a bell for me, I had noticed that material from the Women’s Liberation Music Archive that she was discussing, had been part of a touring exhibition, Music and Liberation 1970-1989, at Glasgow Women’s Library, a project that was coordinated by Withers. I had previously researched Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp (a peace camp established in the early 1980s by women, to protest nuclear weapons being stationed at Greenham Common in Berkshire, England) at Glasgow Women’s Library and come across music and activism as a particularly interesting and under researched part of the Women’s Liberation Movement. As a history student I always had a particular interest in ‘bottom up’ history and oral histories. As I am now attempting to move into the field of heritage, my interest has often been drawn towards immaterial, or intangible forms of heritage. Seeing as Withers’ project is entirely based on online music archives, I was keen to find out more.

Intangible Heritage?

In her lecture, Withers discusses her research into the cultural heritage of the female music making communities in the UK during the Women’s Liberation Movement (1970-1989). She argues that ‘DIY cultural production’ by women within a feminist social movement can be defined as intangible cultural heritage. At the time of the lecture, Withers was the trustee of the online archive and her aim was to both create these ephemeral fragments as artefacts and disseminate them on a digital platform by using blogs.

The women’s liberation movement was fairly widespread and far reaching in the UK, it can never be categorised as relating to one city or one place when discussing the movement as a whole. Withers shows how this kind of heritage is not necessarily tied to one place but rather it is tied to a group of people and a social movement. Withers discusses the ephemeral nature of the women’s music archive in opposition to how popular music is ‘heritagised.’ She reminds us that these forms of music were created before the explosion of DIY culture in the UK in the 1980s, so these women would not have used recording studios and would have largely created music in squats or temporary accommodation. For this reason, the archive is not tied to a specific place and cannot be ‘plaqued’ because there are little physical records and recorded artefacts. The archive largely consists of recorded remains of performances and barely any finished products.

Traditional Western accounts of ‘tangible’ heritage tend to emphasise the material basis of heritage and attributes an inherent cultural value or significance to these ‘things.’ However, Withers’ research provides a new angle on the discussion of intangible heritage. She discusses the fact that she uses the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage as a tool. Intangible heritage is often associated with non-industrial societies so her research differs to the way that intangible heritage is usually theorised. Similarly, intangible heritage is not usually used to protect the cultural heritage of political traditions. However, she believes it is a useful tool for thinking about forms of culture that need to be protected outside of the most dominant ones.

I found it useful to think of Laura Jane Smith’s idea that ‘all heritage as inherently intangible,’ when thinking about the cultural production of the Women’s Liberation Movement. When we look at it this way, the importance is placed on the affect of heritage rather than the cultural object itself. For example, the tools that the women used to make their music were useful but they were not ‘heritage,’ rather the act of playing their music is ‘heritage’ as well as the act of re-interpreting their music is performing heritage.

‘Putting the ‘disco’ into ‘discourse’’

Smith believes that the ‘real moment of heritage is the act of passing on and receiving memories.’ Withers discusses an example of this process when it comes to the Women’s Liberation Music Archive; Rachael House’s Feminist Disco, an installation featuring the artist DJing with singles from a dansette record player, as well as inviting guests to perform with the intention of initiating discussion about the transmission of feminist musical memory. Withers presentation at this event gave people an opportunity to listen to the music from the archive, thus passing on the memory and being able to discuss its implications in the present day. It is interesting to see how Withers’ work was translated for an art installation and how an artist and scholar who are working within the same discourse could draw attention to heritage as a form of activism.

Re-interpreting Music, Performing Heritage

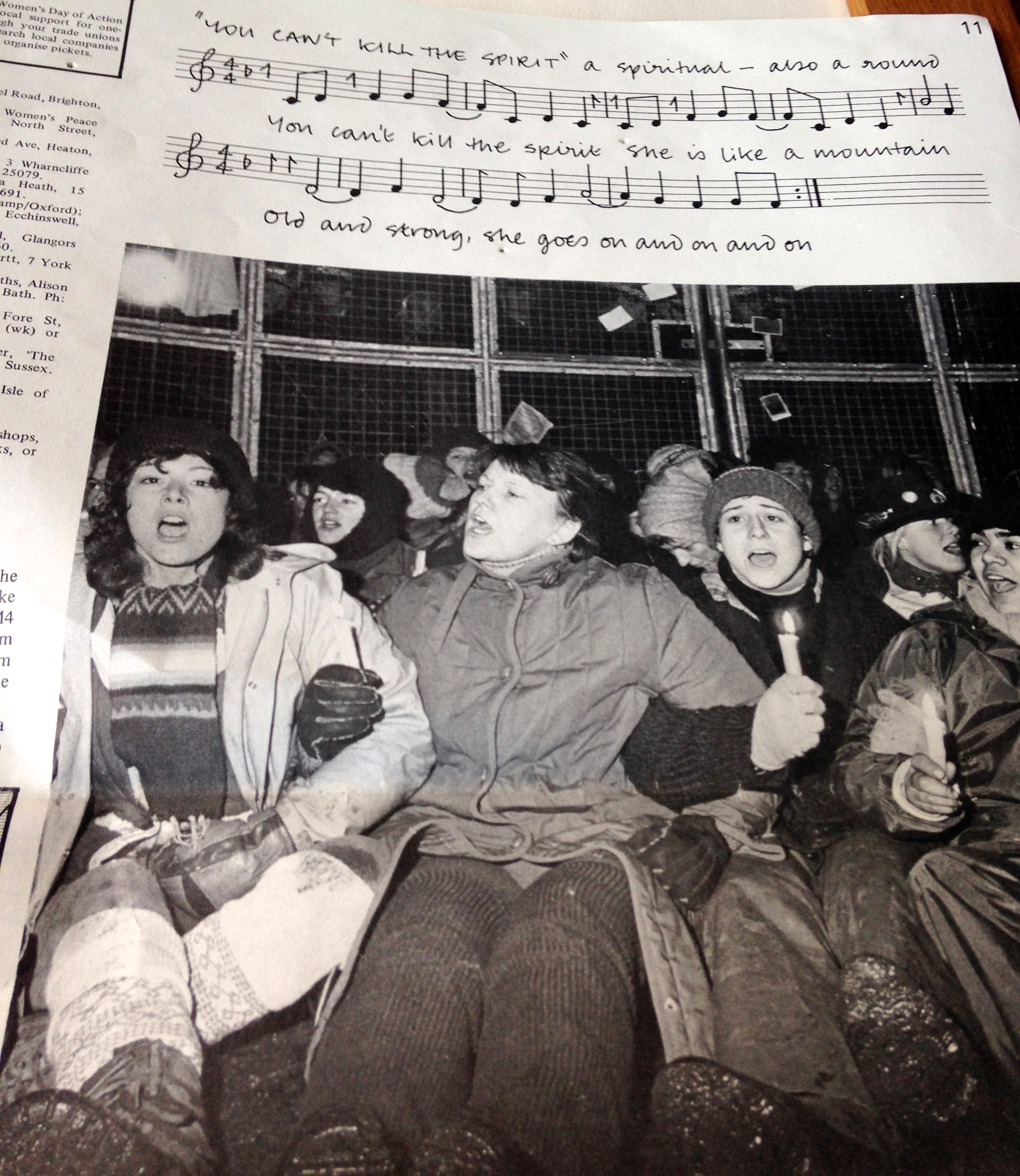

I mentioned earlier that my interest in music and the women’s liberation movement had been triggered by the material I found on Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. (The Greenham Common songbook is now available to download on the Guardian website.) However, there is still little footage of the women at Greenham Common actually performing these songs. In the women’s library I came across the written form of some of the songs performed by the women in a newspaper, The Greenham Factor, produced by the women at the camp, you can see it in the image below. Being a musician myself, as I read the sheet music, I wondered what it might be like to play this music myself. Whilst I never actually did this, (maybe I should do it now!) I now realise that perhaps if I had, I would have been performing heritage myself, the heritage of the women who had lived in Greenham Common, interpreting it myself many years later.

This idea of ‘transmission of practice’ is something that the women in the Women’s Liberation Movement had already considered themselves. Withers discusses how the women learned the techniques of the established music scene of the time but appropriated it for the advancement of women’s culture. There was no deconstruction like other ‘anti-establishment’ forms of music at the time like punk, rather they learnt traditional techniques with the intention of appropriating them to create their own non-commercialised specific women’s culture.

Withers discusses how it is often difficult to learn how the melodies would have sounded but that this was never intended to be a problem, rather their music was always meant to be re-interpreted, rather than consumed. They wanted people to play it, it was never intended to be just one ‘thing,’ they wanted it to be an expression of women’s culture, however each women wanted to demonstrate and interpret this.

Music is often thought of as a way to have ‘fun’, in her lecture withers asks,

‘how can we have fun if there’s sexist music playing at the disco?’

making it clear that music making for these women was a deeply political activity.

Opposing the patriarchy and opposing the ‘AHD’

Smith’s term Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD) refers to the traditional description of Western national and elite class experiences indicating what should be deemed as heritage. She argues that we should try to move away from such descriptions and view heritage from alternative angles. Can we draw parallels between the Women’s Liberation Movement as a grassroots social movement attempting to deconstruct the established order and the attempts to move away from the ‘AHD’? Withers draws out the idea of heritage as something more self-identified rather than self-chosen in opposition to the ‘AHD.’ The way that the Women’s Liberation Music Archive was assembled and intended to be used opposes traditional forms of heritage.

Withers views the music making process as heritage, rather than the finished product, of which there are few in this case. The way that the digital music archive can be used is a continuous process which helps to keep it alive in the present and shows that heritage is not something that is fixed. She refers to digitally re-enacting (but not like historical re-enactments), as a way to bring the past to life through connecting the past, present and the future.

By grasping transient forms of cultural production and making them into an artefact, Withers shows alternative ways of dealing with intangible heritage on a contemporary platform, a kind of ‘heritage activism’ to not only give a voice to a marginalised group but also to bring into the present and recover an ephemeral heritage that could have been entirely lost.

Title Image: Photograph by Justin Warman.

Inserted Image: author’s own.

Works Consulted:

D. Withers, Re-enacting Process: temporality, historicity and the Women’s Liberation Archive, International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol 20:7-8, (2013).

L.J. Smith, Uses of Heritage, (Routledge, 2006).