Written by Anastasia Campbell

Introduction

From 1941 to 1945, on the border of the towns of Amersfoort and Leusden in the Netherlands, a Nazi prison camp was situated. The transit camp held up to 45,000 prisoners (Kamp Amersfoort 2018). In 2004, a memorial was built on the site of the camp, to encourage reflection on the past and ensure those mistakes are not repeated. Additionally, in 2021, a new museum opened as a continuation of the monument, showcasing the life stories of some of the prisoners as well as the archeological finds made at the site.

In many ways the memorial manifests some rather familiar approaches to the memorialization of the World War Two experience. Specifically, the architectural decision to use metallic and rusted-looking materials in the construction of the first memorial building, are an allusion to the corroded, metallic materials often observed as relics of the war. The new museum interior also plays with the sense of confinement and darkness required to translate the menacing and horrific atmosphere of the time. Yet, in many ways the internal structure and operation of the memorial are rather different when compared to memory organizations in the epicenter of urban environments. Within this text I will compare the National Monument Kamp Amersfoort to the GULAG History Museum in Moscow. Whilst I realize that these are two drastically different contexts, it seemed interesting to compare the work of the two organizations, which deal with a very similar topic and themes while operating in quite different ways. Upon reflecting on the potential causes of these differences, it seemed that the root might be the geographical locations of the sites. In turn the relationship between traumatic histories, geography and architecture will be discussed.

Commonalities

To begin with, it would be helpful to outline the commonalities between the two institutions. It is apparent that both deal with a dark historical period in the history of the world and Europe in particular. Kamp Amersfoort is focused on telling the story of the victims of World War Two, including political dissidents, Jewish citizens, Roma and prisoners of war (including at least one hundred Soviet p.o.w.). The GULAG Museum tells the story of Soviet labor camps, which carried a deeply exploitative character with the aim of repressing any potential opposition to the regime, often even without a cause for suspicion. Much emphasis is put on the period of Stalinist repressions, which overlapped with the period of the Second World War.

Moreover, both places chose a similar, and increasingly popular approach to tell these dark histories. Both emphasize the importance of memory and the story of individuals. Both permanent expositions are comprised of personal narratives, personal belongings and unique characters and experiences. This approach is appealing as it most effectively captures the multiplicity of those dark environments as well as highlighting the value of human life.

As hinted above, the architectural and design decisions are also similar. Both exhibitions are located underground, and both create the effect of darkness and oppression, enhanced by a feeling of loss and confusion. The main buildings, where archives are held and research work is carried out, are characterized by an industrial, rusty design.

National Monument Kamp Amersfoort

Underground exhibition at Kamp Amersfoort

GULAG History Museum Moscow

Heritage Expertise

Thus, at first glance the two sites seem to serve a very similar goal and use common techniques and design decisions. However, the two organizations differ dramatically in their functions and public impressions Firstly, the GULAG museum is simply larger in size and scope. Consisting of five floors, one dedicated to the permanent exhibition and one floor dedicated to the archive and research work. Meanwhile at the national monument the whole team, including the director and research group fit in one small office space.

Both institutions rely heavily on the help of their volunteers, yet again, in rather different ways. Whereas the research team of Kamp Amersfoort mostly consists of volunteer workers, who carry out the tasks implicitly associated with ‘heritage experts’ (Hølleland and Skrede 2019). These tasks include the creation of a data base, identifying dead soldiers, contacting impacted families, carrying out interviews and even archeological work. All these activities are carried out by unpaid volunteers, many of whom are representative of the older generation of people, retired from their previous, often unrelated occupation. It is unclear to me why exactly this is the case, but very possibly due to restricted government funding. Whilst in the GULAG museum this work is done by individuals educated within the cultural-historical field and who are between the ages of 30-50. Volunteers simultaneously engage in the more social missions of both of the discussed sites, such as helping in caretaking of the elderly whose families were impacted by this dark history. Or by transcribing documents and interviews that capture the devastating stories of characters shown in the museums or its research projects.

Having the opportunity to have worked in both organizations, it at first seemed rather exciting to see the ‘non-expert based’ approach of Kamp Amersfoort. This was, in fact, one of the first differences that stood out. The small group of people I worked with are all volunteers deeply passionate about the topic. Many of them started this work after retiring from their original jobs. Few are even war and army veterans themselves. It seemed meaningful to have this serious responsibility granted to people who have finished working, as it is a positive way of engaging a part of society that often feels excluded from newly developing social projects. Furthermore, many of these individuals also feel a personal connection to the time, due to their parents or relatives.

Nevertheless, after working for some time at the Monument, it soon became apparent that the activities undertaken at this site would take far longer than anything done at the GULAG museum. Much of the Kamp’s archive itself is not documented and much of the progress relied on long lasting coordination with various other institutions. Our team often lacked the tools, authority or knowledge to resolve questions that arose. Due to the small scope of the team, the labor could not be divided as effectively as at the GULAG museum, where there is a separate unit for all the different projects and directions required. This realization reminded me of the article by Hølleland and Skrede on expertise. Whilst there is of course a degree of a danger in gatekeeping and detachment due to the prevalence of expert based work, neglecting it fully, out of normative social ideals, may be harmful for the potential of the project (2019: 825). Experts help to simplify the process, make it more effective and allow for more fruitful engagement from the side of non-experts who enter the environment surrounded by people who can give concrete guidance. It is my personal belief that this becomes even more necessary in the field of traumatic memory. It is integral to educate and engage as many people as possible and as fast as possible, in order to make the connection with the contemporary environment and initiate change for the better. It becomes even more important in a time like the pandemic when it has become so challenging to visit such educational sites.

Geographies of Trauma

The thought of visiting leads to the central point of this comparative discussion. National Monument Kamp Amersfoort is located on the border of the town and there is only one bus, every hour, that travels from Amersfoort Central Station to the isolated memorial. The GULAG history museum is located in the central area of Moscow with a plethora of travel options to the site (metro, buses, cars and even bikes, which are not standard travel method for Moscovites). It has become rather apparent to me that the reason the GULAG Museum is so much wealthier, engaging, professional and popular is predominantly due to its strategic location. Whilst Kamp Amersfoort becomes far easier to ignore and requires a genuine interest and knowledge in the topic to bother reaching. This has an impact on the audiences who make it to the site and the employees and volunteers who are willing to work at the site. It is natural that the GULAG museum will attract a younger and more professional group of people to work there, and in turn due to its increasing popularity gain the resources to cultivate socially meaningful projects (with extra experts coordinating them). Mainly because that is the group most attracted to large metropolitan city centers. Whilst the isolation of the Kamp, and it’s slower pace with limited social media involvement, make it difficult to grow or transcend its message to a wider audience, being an attractive place of un-intensive work for a passionate but small group of people.

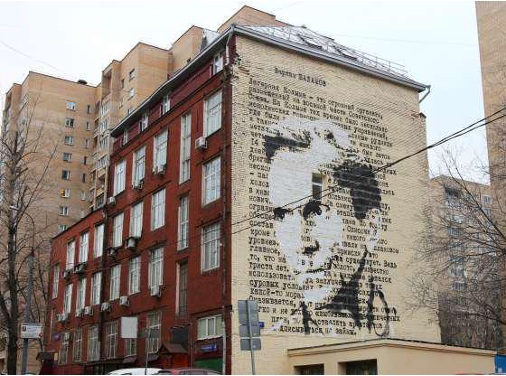

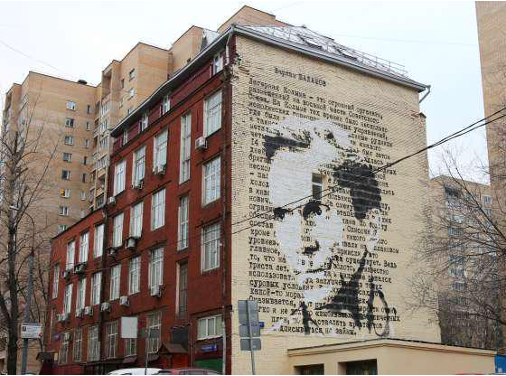

Furthermore, it appears to me that the scope and location of the museum or a memorial are something that interact with how traumatic memory is preserved within the greater landscape. For example, whilst not in line with official narratives, reminders of the traumatic memory of the Second World War and specifically GULAG camps are embedded in the architecture of Moscow.

Meanwhile, it appears that in towns like Amersfoort, or even Amsterdam, the engagement of the city into this history is rather situated and minimal. In the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam one can observe many reminders of the dark past, but street art, statues and stories are not easy to stumble upon in the city environment. To me this is a shame, as museums and monuments should have the ability to interact with their respective environments in a creative way and echo each other in their messages. The National Monument Kamp Amersfoort has much potential for this, seeing as it is located on the site where the traumatic history took place. Yet in many ways it seems that it is simply a “monument” in every sense. It is rooted in a fixed and isolated location, which lacks a dynamic character and thus the ability to spread the important stories and messages it contains.

None of this is to say that the work of the GULAG Museum is ‘better’, rather this blog aimed to reflect on how being located in the city center provides the museum with more opportunities in fulfilling its missions and duties. Furthermore, it must always be remembered throughout discussions concerning the GULAG history, that regardless of how big or well-functioning the museum is, it must partake in the inevitable act of self-censorship according to the official narrative of the Russian government. For example, it is not possible to directly comment on any contemporary events with even a slight hint of a comparison between the horrors of the past and the difficulties of the present. It is also not possible to note the deep involvement and responsibility of Stalin in exacerbating the labor camp system in the USSR. As this does not align with the contemporary narratives that often glorify his character. Overall, it is always important to keep note throughout this comparison that the National Monument Kamp Amersfoort may not have the same budget and immediate possibility for growth, it is situated in a far more liberal democratic environment, allowing its audiences to engage in more fruitful discussions of the past.

References

Hølleland, H., Skrede, J. (2019). “What’s wrong with heritage experts? And interdisciplinary discussion of experts and expertise in heritage studies” International Journal or Heritage Studies, 25(8): 825-836.

Image Credits

Images of Kamp Amersfoort building

Inbo (2021). “Camp Amersfoort, Leusden” https://www.inbo.com/nl/projecten/kamp-amersfoort-leusden Consulted 14.05.201

Underground plan of exhibition Kamp Amersfoort

Archdaily (2021). “National Monument Kamp Amersfoort” https://www.archdaily.com/961105/national-monument-kamp-amersfoort-inbo-bv?ad_medium=gallery Consulted 14.05.2021

GULAG museum building

Ru-Travel (2016). “Москва. Музей истории ГУЛАГа – Moscow. GULAG history Museum” https://reports.travel.ru/letters/2016/03/252715.html Consulted 14.05.2021

Picture indicating GULAG exhibition

Афиша – Afisha (2021). “История ГАЛАГа в судьбах людей и истории страны – History of the GULAG in the destinies of people and history of the country”, https://www.afisha.ru/exhibition/221473/ Consulted on 14.05.2021

Picture of Wall with drawing

ГодЛитературы.РФ, YearofLiterature.RF (2015). “Варлам Шаламов появился на стене – Varlam Shalamov appeared on the wall”, https://godliteratury.ru/articles/2015/12/12/varlam-shalamov-poyavilsya-na-stene Consulted on 14.05.2021